- LAND USE: TRANSIENT ECOLOGIES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

Case Study: Vietnamese Border Markets on the Czech Border

At the Czech-Austrian border near Hatě, 2010

INFORMAL STREET TRADE AS A BORDER PHENOMENON

This study focuses on the border regions of Austria and former Czechoslovakia and the rise of distinct border economies over the last twenty years. Investigating the properties of this former iron curtain border we look at the spatial implications of the border as a set of changing conditions rather than an absoluteness, and how these changing characteristics can influence social, architectural and urban development.

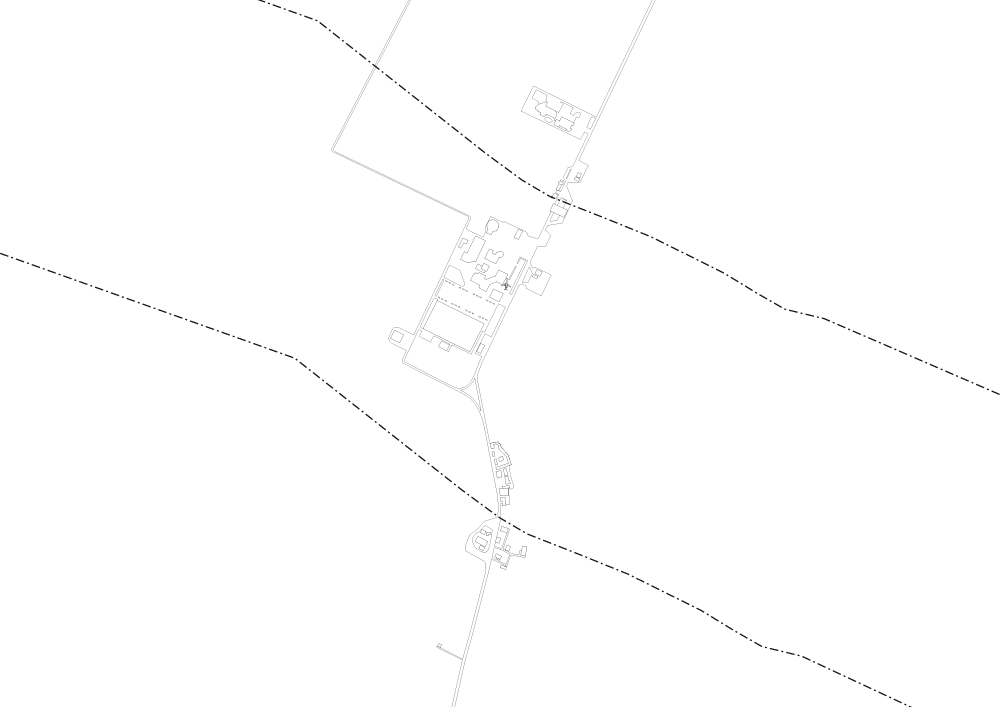

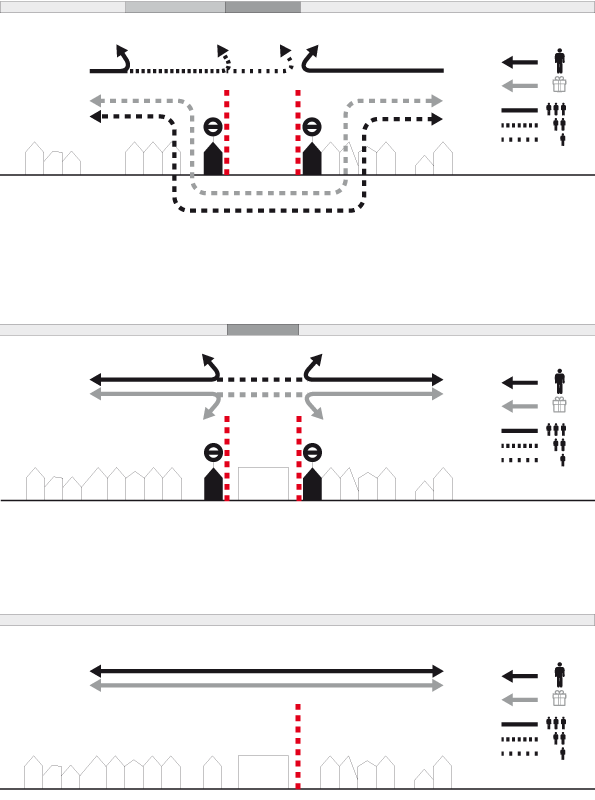

Focusing on Vietnamese street vendors and their highly specific strategy of economic survival in those border regions, we try to follow a strict cartographic approach, leading to a series of partly speculative, partly documentary maps complemented by explanatory text and photographs.

After WW II a heated political conflict arose between the USSR and its satellite states, the so-called Eastern Bloc, and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States and its allies. A conflict of military tension, proxy wars and economic competition that would continue for the next 25 years, varying between periods of relative calm and high international tension. As part of the Eastern Bloc, Czechoslovakia shared an insurmountable 574 km border with Austria. After WW II, existing border crossings were either shut down or protected by massive security measures, formerly daily used footpaths and smaller crossings were made impassable and the border heavily fortified.

In 1950, a 2 km wide strip of borderland on the Czechoslovakian side was declared a restricted military area and was only to be entered by military personnel. The rare entry and customs checks took place behind this strip of empty land. Existing settlements were destroyed and any tracks of former settlements covered. Adjoining this restricted military area was a strip of land, up to 12 km wide, only accessible and inhabitable to citizens with special permission. On the Austrian side, most border controls were relocated further inland and despite the possibility of settling all the way to the border the immediate border zone was mostly waste land. The cross-border movement of goods and people was almost completely suppressed and attempted illegal border crossings severely punished. The border developed from a single line into a strip along the Austrian and German border measuring several kilometres in width.

Location(s): Austria-Czech Border On-Site Collaborator:Klaus Molterer

Joachim Hackl

Visualisations: Klaus Molterer

Joachim Hackl

Photography: Klaus Molterer

Joachim Hackl

Christoph Wieser

Peter Mörtenböck

Helge Mooshammer

Results of this case study were published in:

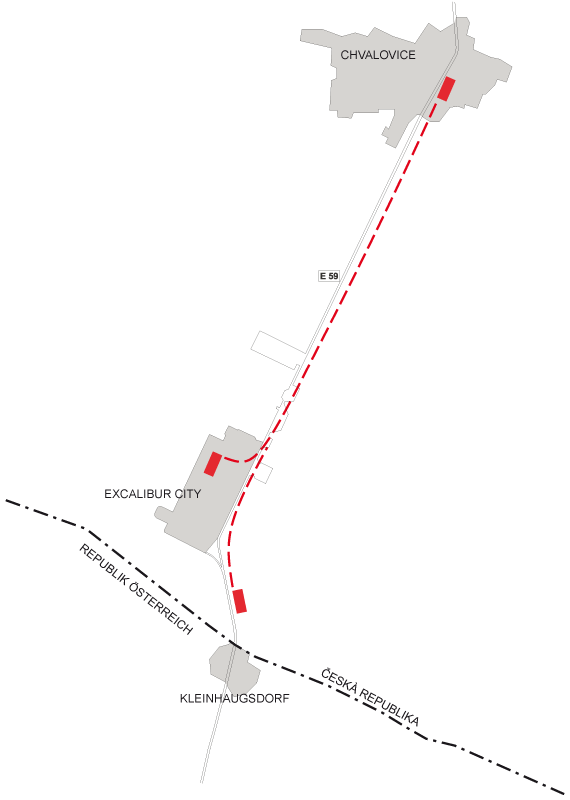

After the Collapse of the Iron Curtain, starting June 1989 with the Hungarian border, the nature of the border as this mentioned strip turned out to be crucial for further economic and social development of the adjoining areas. The opening of the border allowed for a bidirectional border crossing as well as the exchange of goods under certain customs restrictions. The unique situation along the Czechoslovakian border allowed the development of duty-free shops set in between two customs posts enabling the sale of goods exempt from taxation for a fraction of the Austrian price level. The first duty-free Shop, named “Excalibur City”, opened in 1992 on the grounds of former Haté, one of the villages demolished during the clearance of the border area. The economically exceptional position led to massive profits during a time when administrative competences along the border were unclear, allowing for a constant expansion of “Excalibur City”. During the first years the annual business volume added up to €18 million, achieved mostly through the sale of highly taxed goods such as cigarettes and alcohol.

Crossing the Czech border coming from Vienna on the E59, the first striking appearances are small shanty-town-like barracks on the roadside right after the Austrian border. Vietnamese merchants are selling garden gnomes, shoes, clothes, knives, CDs, DVDs, fireworks and groceries at their small market stands to migratory customers, keeping the prices negotiable. Extensive advertisements promise entertainment in establishments named “In Flagranti“, “Moulin Rouge“ or “Sankt Pauli“. Passing “Excalibur City” and the Czech border, these establishments are scattered along the highway. The advertisements, almost exclusively facing drivers coming from Austria, promote “neue Mädchen“ (fresh girls) and promise 30 minutes of entertainment for €29. Chvalovice, the first village after the Czech border, is covered with roadside billboards, promising just the same complemented by advertisements for cheap food.

Following the eviction of the German speaking minority after WW II, the area was revitalized by resettling inner-Czech citizens to those border areas. The official population count in 2004 was 446 inhabitants, although the estimates of actual numbers are much higher due to the rapid internationalization after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Prostitutes from former Eastern Bloc countries are temporarily working without residence permits, Austrian women are earning money in anonymity across the border, while a strong Vietnamese minority is living in rented apartments and until 2004 coined the village with their vital trade activities. These border-economies are examples of highly specific survival strategies beyond the “Duty Free” concept, which lost its legal foundations in 2004 with the Czech Republic’s membership in the EU.

The constant expansion of “Excalibur City“ from a single market stand to a shopping complex can be described as a programmatic expansion of its original business area, with a gradual zoning of differing infrastructure and levels of informality. Starting with the newest expansion, the “Freeport Marken Outlet”, an independently run outlet mall of international standards, we can observe a gradual decline of infrastructural services and, vice versa, an increase of informality and decoration. “Chinatown”, the area appearing to be strongly related to informal trade activities, is a canopied market consisting of approximately 120 market stands mostly run by the local Vietnamese minority. The organizational structure of this market seems to be similar to the roadside markets across the border. These small-scale retail activities seem to be a widely spread phenomenon along the Czech border to Austria and Germany, as well as a characteristic of the Vietnamese minority in the Czech Republic.

The Vietnamese minority represents the third largest group of immigrants after immigrants from Hungary and Slovakia, and its history goes back to WW II. After WW II, Vietnamese students, trainees and workers travelled to Czechoslovakia within the framework of workforce exchange programs between communist countries. The stay of Vietnamese guests was highly regulated, limited to certain economic areas, and only allowed for a minimum of individual freedom. The host country not only provided employment, but also housing, insurance and further training. By 1970, about 2000 Vietnamese immigrant workers were staying in Czechoslovakia, a number that should multiply after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Immigration experts estimate that between 70000 and 120000 Vietnamese immigrants worked in Czechoslovakia during the 1980s, all in the framework of the mentioned workforce exchange program. The reason for this rapid growth of Vietnamese immigration can be observed on a global scale.

During WW II, Semtex, a widespread explosive, and the Eastern-European counterpart of the American C4, was developed and produced in Pardubice, 100 km east of Prague. From there, Semtex was exported to northern Vietnam and to the Vietcong during the Vietnam War as well as other nations of the Warsaw Pact. After 1975 north Vietnam’s debts caused by Semtex import and its weak postwar economy forced North Vietnam to pay back their debts by exporting cheap workforce to Czechoslovakia. The Vietnamese immigrants worked for four to seven years, receiving 40-50% of their loans directly, while the Vietnamese Government received the remaining 60% to pay back their debts. After the collapse of the Iron Curtain the workforce exchange agreement was cancelled. At that time around 13000 Vietnamese citizens remained in Czechoslovakia. While the formerly state owned economy and its enterprises were restructured, most of the foreign workers received small-scale retail licenses. Numbers of the Czech Statistical Office from 2008 account for 66% of Vietnamese immigrants having a small-scale retail license, while only 34% had a regular work permit. In comparison, the second strongest immigrant group in reference to small-scale retail licenses are German immigrants with 33%.

The above mentioned forms of small scale retail benefit from the border situation of the former Iron Curtain, and therefore concentrate along the Austrian-Czech and German-Czech border. Looking at Czech border regions, an almost inverse linear relationship between spending capacity in the bordering regions of Germany and Austria and the Vietnamese minorities’ share of the population stands out. Their economic activities benefit on the one hand from a general economic downturn of Middle-European border regions with former Eastern Bloc nations and on the other hand from generally lower costs of also living on the Czech side of the border. Therefore economically disadvantaged minorities benefit on multiple levels from the location of settlements such as Chvalovice. The above mentioned points led, after 1989, to a strong movement of Vietnamese immigrants, generally a very mobile population group, from city regions to settlements close to the former Iron Curtain.

Until the Czech Republic joined the European Union in 2004, the Vietnamese trade activities flourished in Chvalovice, but EU membership and anti-piracy laws complicated the sale of counterfeit products such as DVDs and Software, back then the major income for the salesmen and -women. Increasing trans-European crime prevention networks enabled crackdowns on counterfeit products and led to the migration of those economic activities into the formerly restricted military area. This spatial relocation mainly concerned two areas; on the one hand a plot on the premises of “Excalibur City”, on the other hand a strip of empty land next to the highway right across the Austrian border.

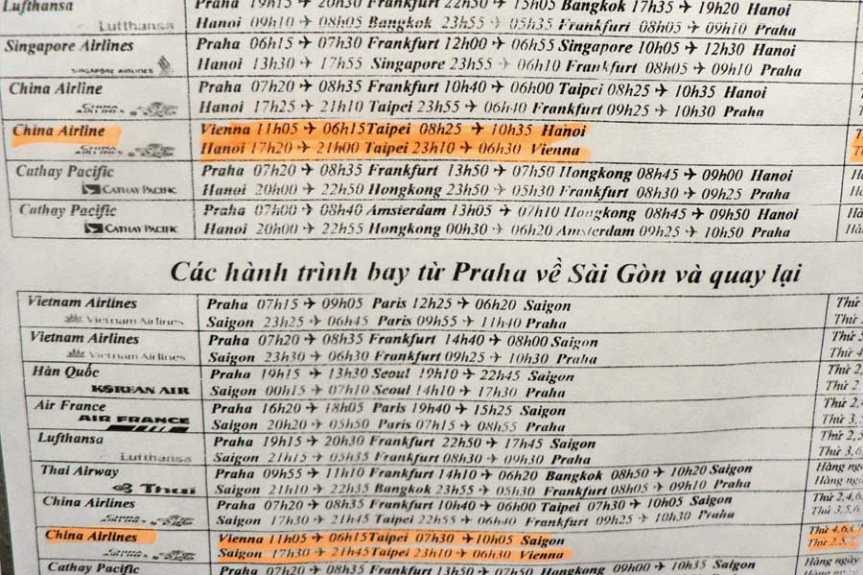

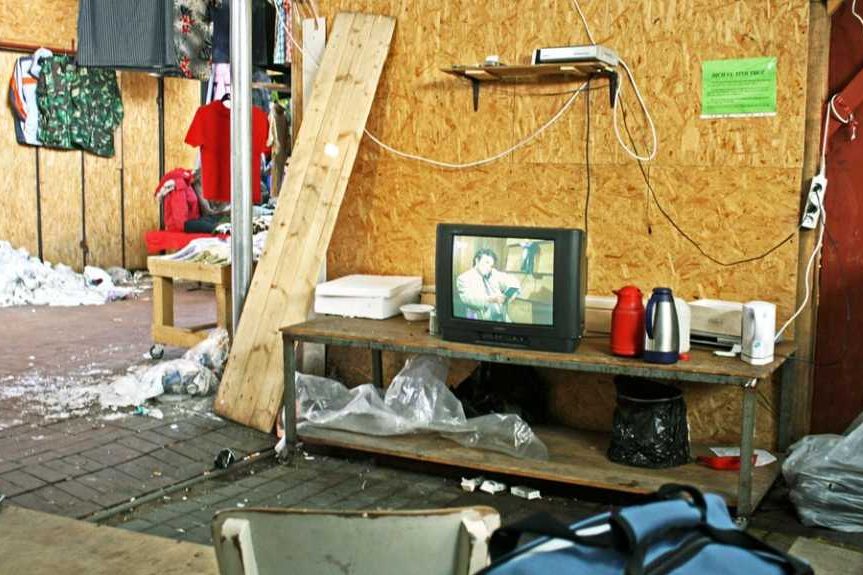

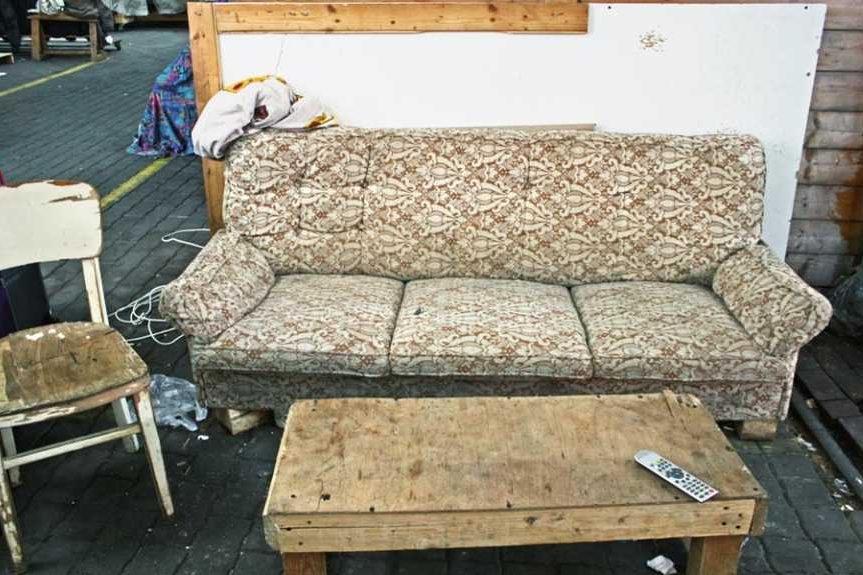

The settlement inside “Excalibur City” is characterized by its originally ordered grid of approximately 120 market stands, subordinated to the plot’s outline and certain special functions, such as a Pagoda used as a stage and a communal area in the centre of the parcel. Little by little, the separate stands were covered up with plexiglass and corrugated sheet iron to form a single roof connecting the stands. At the same time the stands started expanding, gaining retail and storage area. Outside the plot the market started to spread with disused shipping containers and simple huts, containing kitchen, recreation or storage areas. A uniform facade, matching “Excalibur City’s” stage-set-like qualities, was erected out of sheetrock and signals of “Asia Bazar” with some Chinese characters written next to it. Glued to the facade are price lists comparing different flight companies and their prices to Hanoi, and the former Diner-Grill double-decker bus from London has been converted into a wok-take-away. Permanently parked and mostly wrecked minibuses with blind windows are used as a storage area and claim access roads as private space. Regular parking for everyday use is located at the outline of the plot.

Since the European Union passed a new anti-piracy law in 2005, the circulation of counterfeit media products, once the principal source of income, seems to have moved into online platforms. Only the roadside stalls still sell these goods in separate booths, not clearly assigned to one or another stall and, opposed to the regular stalls, not labelled with the owner’s name. Since the Czech Republic joined the Schengen-Region in 2007 the border seems to be disappearing, border controls across Europe have been reduced and Schengen seems to be this vast territory of interconnected high density areas. Despite these obvious disappearance and reinterpretation of national borders, the markets around “Excalibur City” are open all year, and the stall holders spend their days around the campfire playing Xiang Qi, a popular Vietnamese board game.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Klaus Molterer

Joachim Hackl