- TRANS-NATIONALITY: LEGAL ARCHITECTURES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

CASE STUDY: ARIZONA MARKET

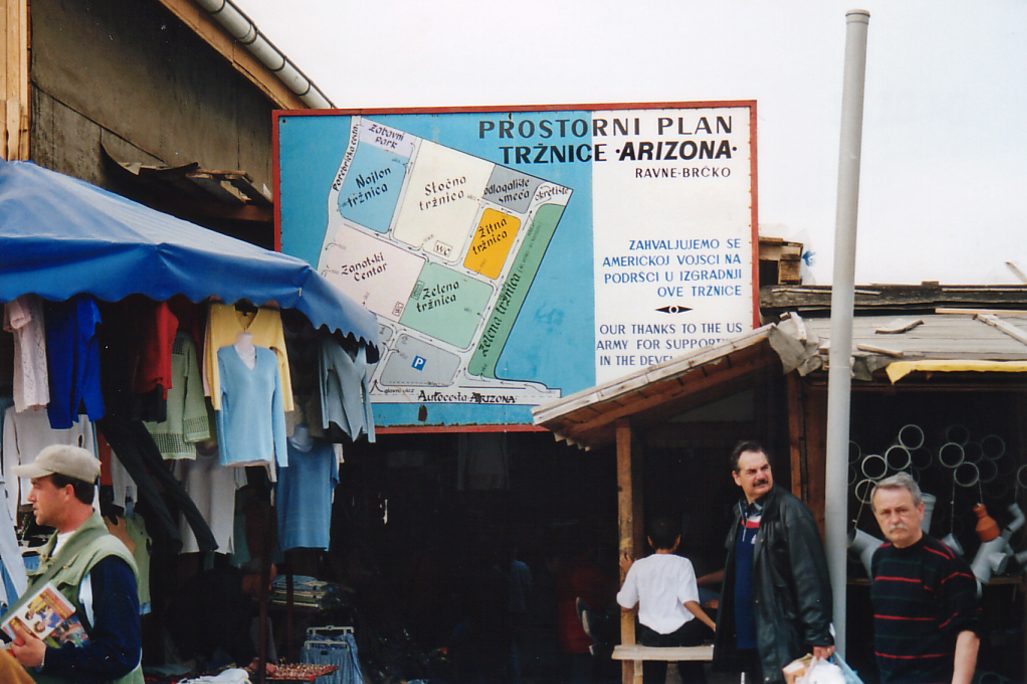

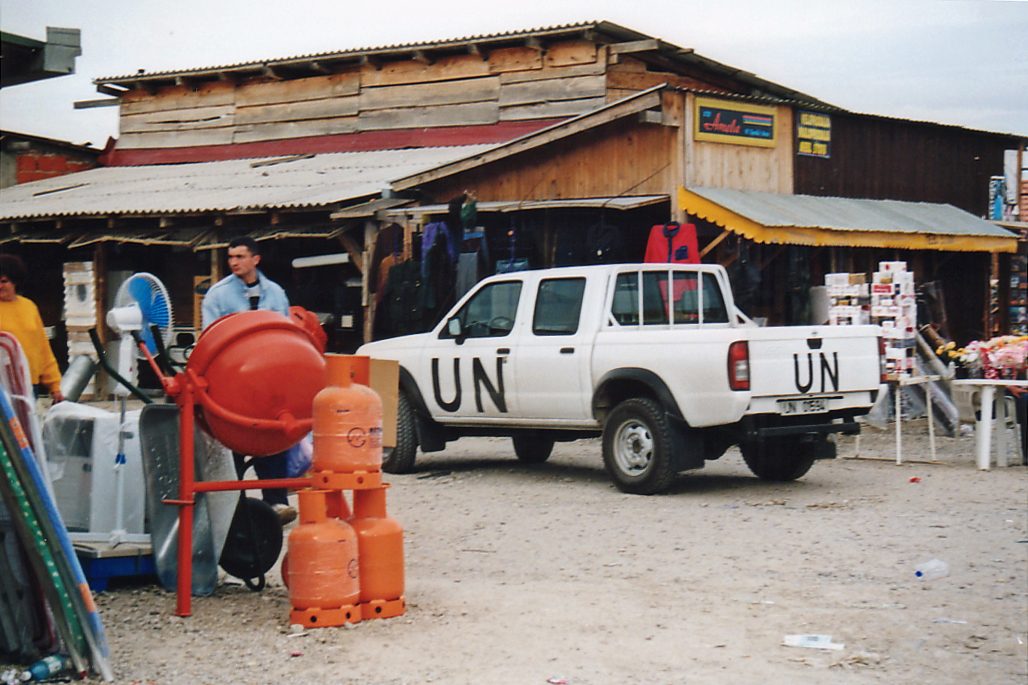

Arizona Market, Brčko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2001 (photos: Azra Aksamija)

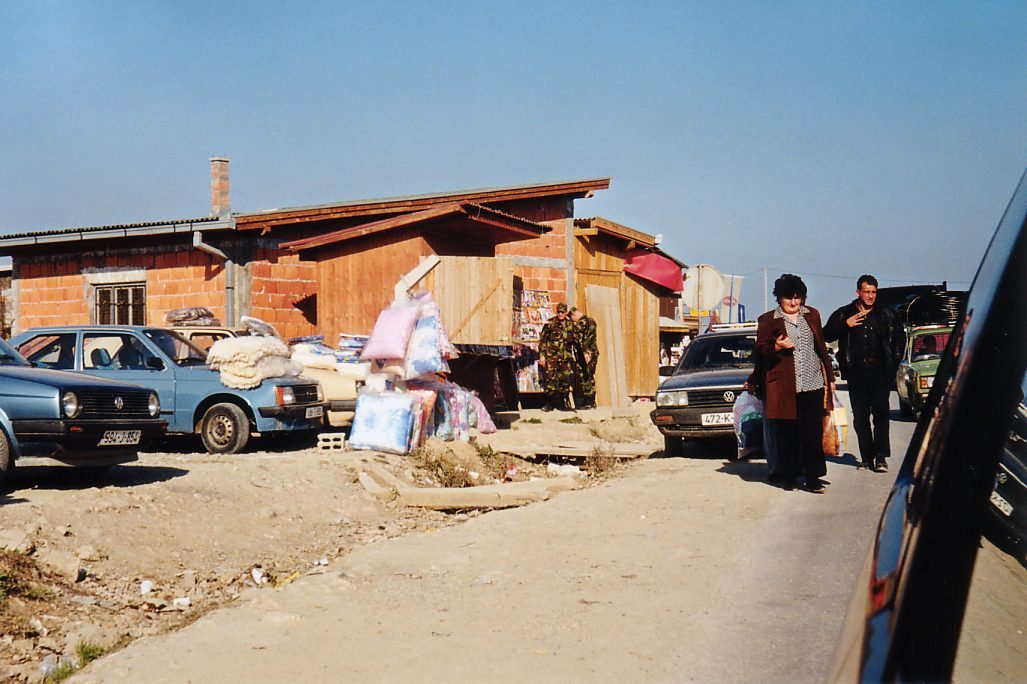

Arizona Market, Brčko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2006 (photos: Peter Mörtenböck, Helge Mooshammer)

ARIZONA MARKET: INTER-ETHNIC COLLABORATION IN BRČKO

One of the most referenced examples of an informal market as nucleus of urban development is the so-called Arizona Market in the Brcko district in the Northeast of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There are a number of different narratives in circulation about what triggered the birth and boom of this vast informal market in war-torn Bosnia. The most widely supported ones attribute its rise to a kind of natural emergence of a free market environment, under the protection of the military presence of the International Community and as desired by the local population.

The strip of land occupied by the present Arizona Market is a part of the war zone that was fiercely fought over by Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian Muslim units because of its strategic position after Bosnia-Herzegovina had left the federal state of Yugoslavia in 1991. The Dayton Peace Accords of November 1995 granted special status to this disputed territory around the town of Brčko, whose future was to be decided in an international arbitration process. It was placed under the direct supervision of a special supervisor from the Office of the High Representative (OHR) of the international community of states for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

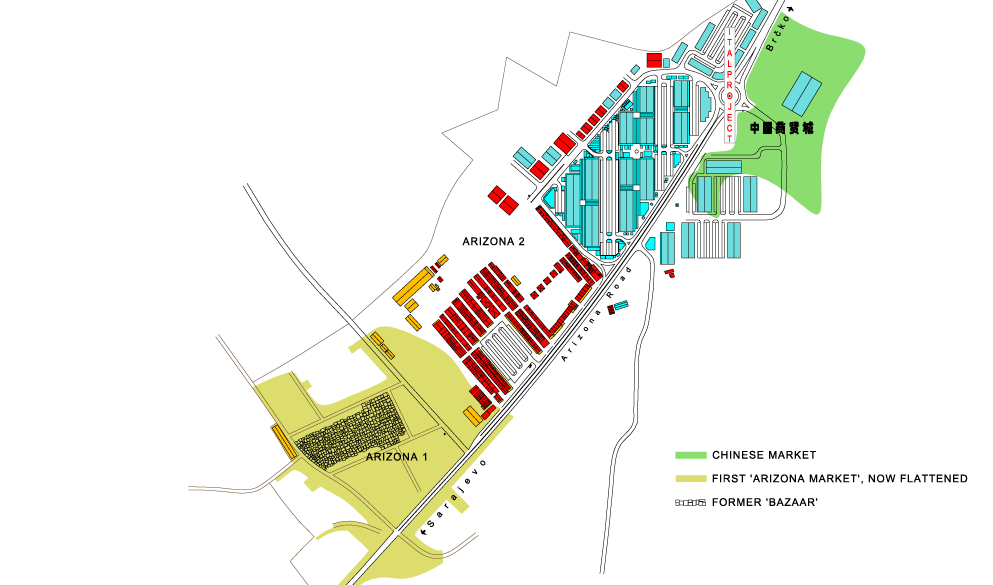

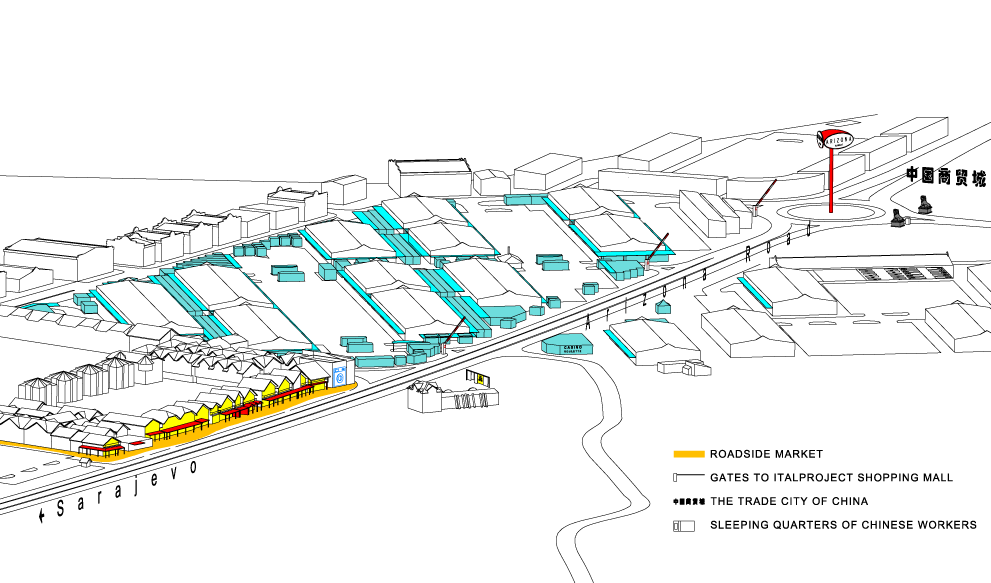

Soon after the local checkpoint at the Arizona Corridor (the code name given to the north-south passage between Bosnia and Croatia by the IFOR/SFOR troops) had evolved into an informal meeting place where cigarettes and cattle were traded and coffee was served at the roadside. It is said, that in 1996 the local commander decided to encourage initial encounters between members of the different ethnic communities by establishing a ‘free-trade zone’, thereby contributing to consolidating peace. SFOR soldiers levelled several hectares of farmland, cleared the mines and supplied building materials. In next to no time, the largest informal market for goods in Southern Europe arose on the opposite side of the road to the checkpoint: with wooden huts, improvised stalls, smuggled goods and bootleg versions of brand-name goods. Textiles, food, electronic products, building materials, cosmetics, car accessories and CDs could all be purchased at favourable prices there.

Decisive for the continued development of Arizona Market was the fact that, unlike most other informal markets, it arose on the open fields with the support of the armed forces. In the years that followed, the continuous growth of economic activities at the site and the self-organisation of a market environment were extolled as a model for promoting the sustained development of communications and community structures between former wartime enemies.

Location(s):Brčko, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

On-Site Collaborator:PETER MÖRTENBÖCK

HELGE MOOSHAMMER

Photography: PETER MÖRTENBÖCK

HELGE MOOSHAMMER

AZRA AKSAMIJA (2001)

Results of this case study were published in:

Supplementing the simple market facilities and mobile sales, the first houses soon arose, presaging the emergence of a self-organised urbanisation process on the site. However, as time went by, ever more bars and motels operating in these huts and houses started to accommodate a form of trade that made it increasingly difficult to sell – at an international level – the success story of peace based on the market economy. For at Arizona Market, the real money was made through prostitution and trafficking in human beings: with women and girls who were being brought in from Eastern Europe. According to reports, they were rounded up on the streets and resold like cattle from one bar owner to the next.

Eventually, on 26 October 2000, the International Community (OHR, OSCE, UNMIBH and SFOR) announced a package of measures designed to purge Arizona Market of such illegal activities. These measures focused on regulating the issue of licences and tax revenues, and relocating the market by June 2001 to a new site that would offer all the necessary facilities and safety features (1). The solution to this ‘abuse’ of the market as implemented by the International Community thus followed the earlier mentioned model of privatisation aided by authorative regulatory measures.

In February 2001, the supervisor ordered the closure of the existing market (2). In December that year, ItalProject, an Italian-Bosnian-Serbian consortium, won a tender to establish and operate a new market. The consortium signed a 20-year leasing agreement with the district administration that granted it the right to retain 100 per cent of the rental income for a period of seventeen years in return for developing the infrastructure. In a later phase of development, a complexly structured economic and trade base for the entire south European area was to be established that would include multiplex cinemas, hotels, casinos and a conference centre.

Italproject offered existing traders the opportunity to rent or buy stalls in module-like rooms. Resistance by landowners and traders to this total takeover was met with compulsory dispossessions. This response was justified with the argument that it was in the public interest to ensure that the district administration of Brčko complied with the agreements concluded with Italproject (3). Demonstrations and road blockades staged to oppose the demolition of the old site were cleared by the police. As most of the landowners affected were Croatians who sought the support of nationalist groups to assert their cause, the maxim of achieving reconciliation by taking economic measures came dangerously close to fomenting an ethnic conflict as a result of what was seen as an arbitrary allocation of economic options.

One of the most striking things about this strategy to regain control over Arizona Market – which ultimately culminated in the ceremonial opening of a new shopping centre in the presence of the Principal Deputy High Representative, the US Ambassador, Donald S. Hays, on 11 November 2004 (4) – was the way the international community, which exercised politico-territorial control, and an international investor co-operated in privatising the public domain of the market. The transformation of the informal market into a shopping centre signalled a critical turning point, revealing the limits of translating between formal and informal systems. The ‘spontaneous’ evolution of a public-urban space in the shape of an informal market surrounded by transporters and huts was replaced by enclosed fee-charging parking spaces. The coming together of diverse cultures was now regulated by fixed opening hours and private security guards.

In only ten years, Arizona Market has been transformed from a space of bare survival into a centre of ubiquitous consumption. What was once a mere border guard post has now become a post-metropolitan territory. Hopes that Arizona Market might become a model for a self-organised town were dashed when a market arose whose existence and development were far more extensively tied up with the presence of the international defence force than that formerly generous gesture to bulldoze a few fields seemed to suggest. The UNHCHR attributes the crisis – the dramatic increase in prostitution and trafficking in women – to, among other things, the presence of over 30,000 peacekeepers in BiH (5). Bosnia was not so much a transit country as a destination for women victims of trafficking. The SFOR troops were not only customers, but allegedly also had their share of the profits accruing from smuggling and corruption. The ‘solution’, based on the model of ‘urban renewal’ developed in the USA in the 1960s (declaring a district a problem area and thus permitting large-scale expropriation in the name of the ‘public interest’), was fostered by the transformation of the legal system in the Brčko district with the help of legal advisers financed by USAID (US Agency for International Development) (6).

Nowadays, Arizona Market is characterised by two things that are ultimately related to one another. Although – or because – the international community has intervened massively in the regulation of the market, the purging of the market by means of centralised controls has been an extremely nebulous affair: on the one hand, for example, Italproject’s Italian lenders are persistently not named and, on the other hand, Italproject refuses to ask where the buyers of new market properties obtain the money they need to make their purchases. Rumours range from assertions of lucrative deals being made by organised veterans of paramilitary associations and the employment of suspected war criminals, to allegations of deals being struck with former brothel-owners who are not content to rent one stall only, but invest in ‘turbo penthouses’ occupying several floors.

The convoluted flows of international money and goods at Arizona Market may have now entered a new phase, yet the form of capitalism that prevails there now is no less ‘rampant’ than it used to be. Its attraction lies in an all-pervading motivation to gain some form of control – ranging from the need to survive, at one end of the scale, to international relations at the other – by seizing anything that is not yet subject to controls. All these many different levels of exchange have created the countless trade situations that one finds at Arizona Market, which promise everyone an opportunity to exploit the market to their own ends, even if this only means purchasing a cheap T-shirt.

(1) Office of the High Representative (OHR) and EU Special Representative (EUSR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, “International Community to clean up trade at the Arizona Market, Brcko”, Press Release (26 October 2000)

Online: http://www.ohr.int/ohr-dept/presso/pressr/default.asp?content_id=4092

(2) Office of the High Representative (OHR) and EU Special Representative (EUSR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Supervisory Order on the Use of Land in Arizona Market’ Press Release, (17 February 2001)

Online: http://www.ohr.int/ohr-offices/brcko/bc-so/default.asp?content_id=5323

(3) Office of the High Representative (OHR) and EU Special Representative (EUSR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, ‘Opening Remarks of Brcko Supervisor on land expropriation in Arizona Market at a press conference in Brcko on 25 July 2002’ Press Release (25 July 2002)

Online: http://www.ohr.int/ohr-dept/presso/presssp/default.asp?content_id=27536

(4) Office of the High Representative (OHR) and EU Special Representative (EUSR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, ‘PDHR to attend the formal opening of the Arizona Market’ Press Release (10 November 2004)

Online: http://www.ohr.int/ohr-dept/presso/pressb/default.asp?content_id=33492

(5) Madeleine Rees (UNHCR Sarajevo), ‘Markets, Migration and Forced Prostitution’, Humanitarian Exchange Magazine No 14 (June 1999). Online: http://www.odihpn.org/report.asp?id=1054

(6) US Agency for International Development (USAID): ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina. ACTIVITY DATA SHEET. FY 2002’. Online: http://www.usaid.gov/pubs/cbj2002/ee/ba/168-031.html

CONTRIBUTOR(S)