- LAND USE: TRANSIENT ECOLOGIES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

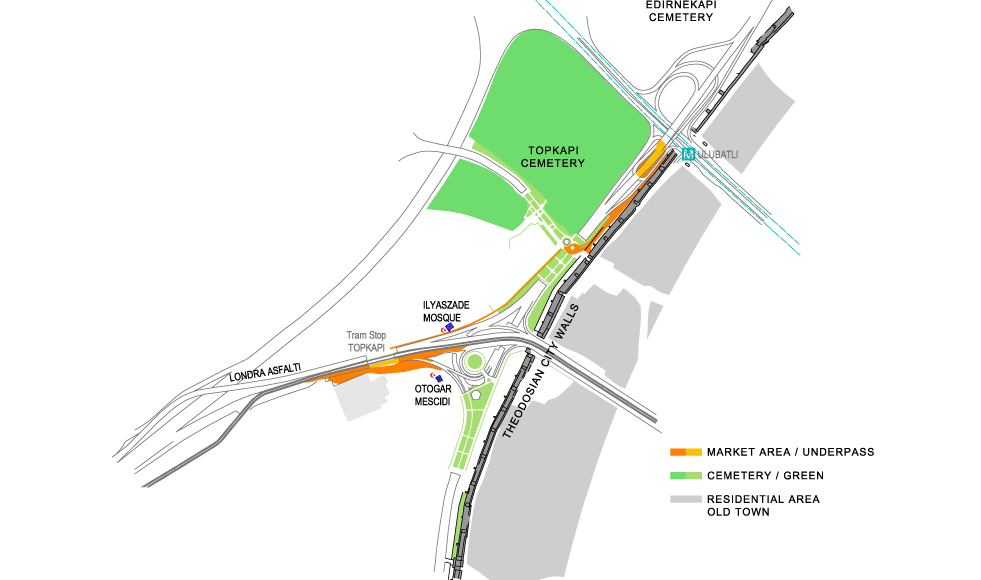

CASE STUDY: TOPKAPI STREET MARKET

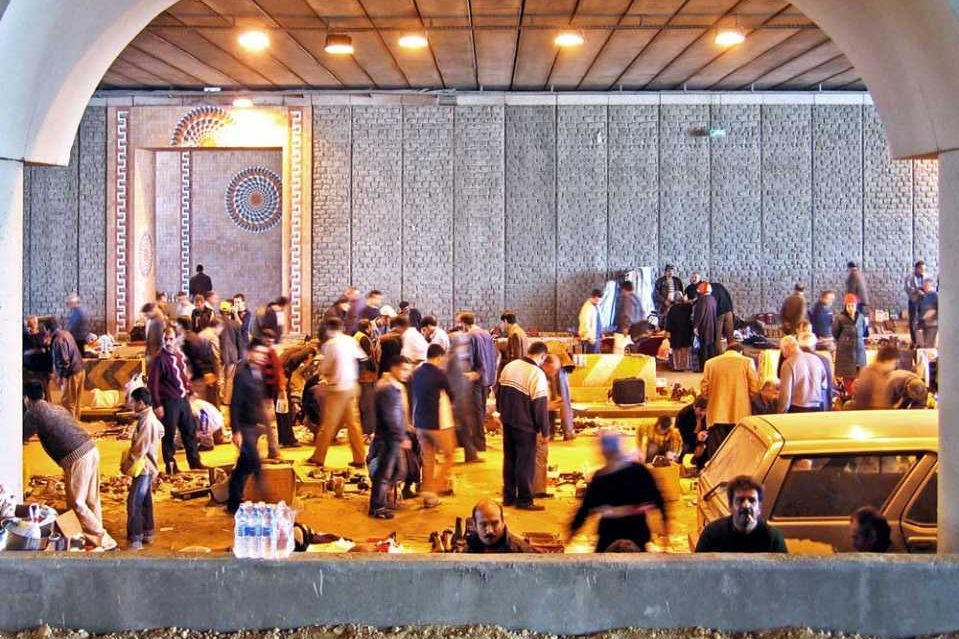

Ulubatlı flyover along the Byzantine city walls and Topkapı and Edirnekapı cemeteries, Istanbul, 2005

GRAND BAZAAR OF ARCHITECTURES

In July 2005, one of the leading forums for international architecture – the 22nd World Congress of Architecture – was held in Istanbul under the motto ‘Grand bazaar of architectureS’. The central theme of the congress was the utopian idea of a pluralistic world in which cultural differences are not a source of animosity and atrocities, but a resource to help people find a way to live together in harmony.

The leading lights in contemporary architectural design presented their models and discussed them in the context of Istanbul’s struggle for recognition as a cosmopolitan city. Outstanding engineering achievements, sustainable planning and cultural heritage formed part of a well-orchestrated protocol of declarations of intent to participate in the exclusive set of global cities. The allegorical motto of the congress as well as its point of reference – the legendary oriental bazaar that leaves no desires unfulfilled – transfigure the socio-spatial challenge posed by a rapidly expanding megacity and its hope that it will be saved by quick responses from architects and urban planners (1).

Outside the tourist centres and escaping international attention lies a very different type of bazaar. It is composed of a vast network of provisional, informal street markets that establish themselves right alongside building sites where urban renewal plans are being realised, beneath terraces of city motorways and next to newly constructed tramway lines. These markets disappear as quickly as they materialise, only to reappear elsewhere. This bazaar is not so much a location for trading goods as a space under negotiation. It is a threatening and threatened space which winds its way through the city from site to site and temporarily uses (as the intermediary user of the newly planned infrastructure) the wastelands along the development axes of the planned city.

Location(s):Istanbul, TÜRKIYE

On-Site Collaborator:PETER MÖRTENBÖCK

HELGE MOOSHAMMER

Photography: PETER MÖRTENBÖCK

HELGE MOOSHAMMER

Results of this case study were published in:

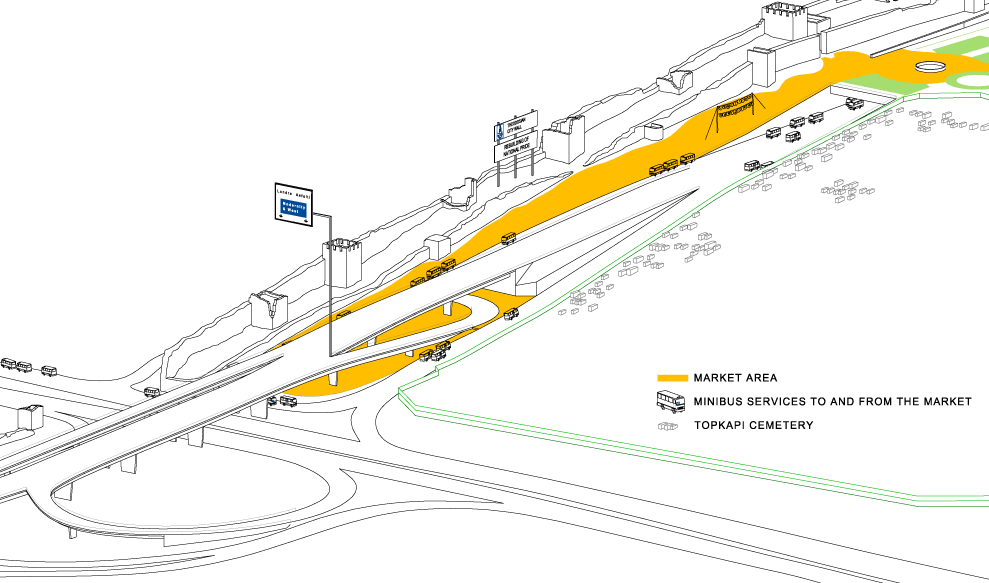

One of these arose in 2005 before the gates of the Byzantine city wall in the district of Topkapı, where the building sites of two of the main enterprises that took on the job of tidying up the city in the 1980s converge. On the one hand, a traffic network of urban motorways has been created there in the style of modernist US urbanism. On the other hand, the 1,500-year-old Byzantine city fortifications have been reinstated there in their original condition. In nationalist literature, their continual decline and the living conditions in the wretched areas bordering the fortifications had come to symbolise both the impoverishment of Istanbul and the stronghold of true Turkish values (2). Between newly delivered and unused building materials, impassable heaps of crushed stone, and 8-lane motorways, a swarm-like mass fills a black market covering several kilometres. Piles of second-hand goods and fabrics are mixed up on bare ground with new TV sets, refrigerators, pieces of furniture and computers. On days when visitors turn out in strength, several thousand people can be seen negotiating this construction site of the new Istanbul.

In stark contrast to this ‘wild’ and bustling accumulation, the whole place is bordered with an immaculate but deserted layout of formal green whose ghostly abandonment is amplified by the garish colour of the artificially irrigated lawn. In 1852 Théophile Gautier wrote about this stretch along the city walls:

‘It is difficult to believe there is a living city behind these dead ramparts! I do not believe there exists anywhere on earth [a thing] more austere and melancholy than this road, which runs for more than three miles between ruins on the one hand and a cemetery on the other.'(3)

The informal market evokes an archaic model of a city that arises organically as trading centre at the junction of transport and trading routes. In the case of Topkapı, however, it is also moving in the shadows of official town planning, which it temporarily turns into a vehicle serving informality. This market makes use of the semi-finished building structures in a way that has less to do with their intended uses or with any conceptions or images of modern urban planning than with unplanned utilisation and the economic situation of the rural population that has migrated to the city. Land has been occupied here on an improvised basis, bypassing the planners. This approach is not based on how things will look after the plans have been realised, but seeks instead to realise alternatives to this process.

The innovatory power of this informal economy is evident not only in its sheer size, but also in its far-reaching ramifications, with all the emerging services systems such as shuttle buses, street kitchens, middlemen, suppliers, livestock selling, the attendant forms of cultural entertainment and ad hoc shooting ranges. With its bizarre combination of modern transport systems, its symbolic sites of a national renaissance, spontaneously arising market activities, rich visual display of the intricacies of legally authorised work, its third market and informal trading, Topkapı represents more than just a coincidental clash of diverse forces. The growing perviousness of official and informal structures, the rampant appropriation of urban space and the accelerated disintegration of cultural territories are typical moments in the evolution of a city structure dictated by the new world economy, in which full control over a territory is no longer a relevant issue. In contrast to the territorially based economic forms, large and small spatial structures are evolving which circumvent the functional separation of space and embed themselves in the prevailing geography as a mesh of networks.

Participation in socio-spatial processes, for which the informal market situated amidst the hustle and bustle of Istanbul stands, echoes the performance – used as a metaphor by Ernesto Laclau – at which we always arrive too late. We live as bricoleurs in a world of imperfect systems whose rules we co-determine and transform by retracing them. It is in this very moment, according to Laclau, that we find the key to (acts of) emancipation: in the middle of a performance that has started unexpectedly, we search for mythical and impossible origins but are unable to rise above the impossible task facing us. What counts, however, is that we struggle and strive to arrive at decisions that have to be made because there is no superordinate monitoring or control system. Running counter to the radical foundation of a democratic society and operational structures sketched out in the great narrations of modernity, a model of political praxis is taking shape that is continuing to develop through a plurality of acts of democratisation (4). At Topkapı market, we only know that the minibus we try to stop by waving it down really is going to stop once we are inside it.

(1) Suha Özkan, “The welcoming speech of the President of the 22nd UIA World Congress of Architecture,” Programme, (Istanbul: UIA 2005), 10f.

(2) Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul. Memories and the City (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 245f.

(3) ibid., 231-2.

(4) Ernesto Laclau, Emancipation(s) (London and New York: Verso, 1996), 79-82.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

PETER MÖRTENBÖCK is Professor of VISUAL CULTURE at the TU Wien, Co-Director of the CENTRE FOR GLOBAL ARCHITECTURE and Senior Research Fellow at Goldsmiths College, University of London.His current research is focused on the architecture of the political community and the economisation of the city, as well as the global use of raw materials, urban infrastructures and new data publics.Together with HELGE MOOSHAMMER, he curated the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021, which explored the theme of “platform urbanism”.PETER MÖRTENBÖCK’s appointment at the TU Wien was preceded by two other offers of a professorship in Vienna – Professor of Architectural Design (Geography, Landscapes, Cities) at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna(2018) and Professor of Architectural Theory at the University of Applied Arts Vienna (2019). Following his professorial habilitation in the field of cultural history at the TU Graz he was immediately offered the position of Professor of Media Aesthetics at the University of Paderborn, a position he held in 2002. Prior to this he was a guest professor of fine art at the University of Art and Design Linzfrom 2000 to 2001, and from 1998 to 2000 he conducted research at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and returned there as a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellow from 2005 to 2007.

HELGE MOOSHAMMER is an architect, author and curator. He conducts urban and cultural research in the Department of VISUAL CULTURE at the TU Wien, is Co-Director of the CENTRE FOR GLOBAL ARCHITECTURE, and Research Fellow at Goldsmiths College, University of London.He has initiated and directed numerous international research projects focusing on issues relating to (post)capitalist urban economics and urban informality, including the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) projects “Relational Architecture” (2006-09), “Other Markets” (2010-15) and “Incorporating Informality” (2018-23). In 2008 he was a Research Fellow at the Internationales Forschungszentrum für Kulturwissenschaften (IFK) in Vienna. He has taught at a number of institutions, including the University of Art and Design Linz, the Merz Akademie Stuttgart, and Goldsmiths College, University of London. HELGE MOOSHAMMER’s current research is focused on architecture, contemporary art and new forms of urban sociality in a context shaped by processes of trans-nationalisation, neo-liberalisation and infrastructuring. Together with PETER MÖRTENBÖCK he curated the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021, which explored the theme of “platform urbanism”.