- IMPROVEMENT

- FWF

- 2018-2023

- Incorporating Informality

Karama Market, Dubai, 2023

URBAN REGENERATION IN DUBAI – INFORMALITY OUT OF SIGHT

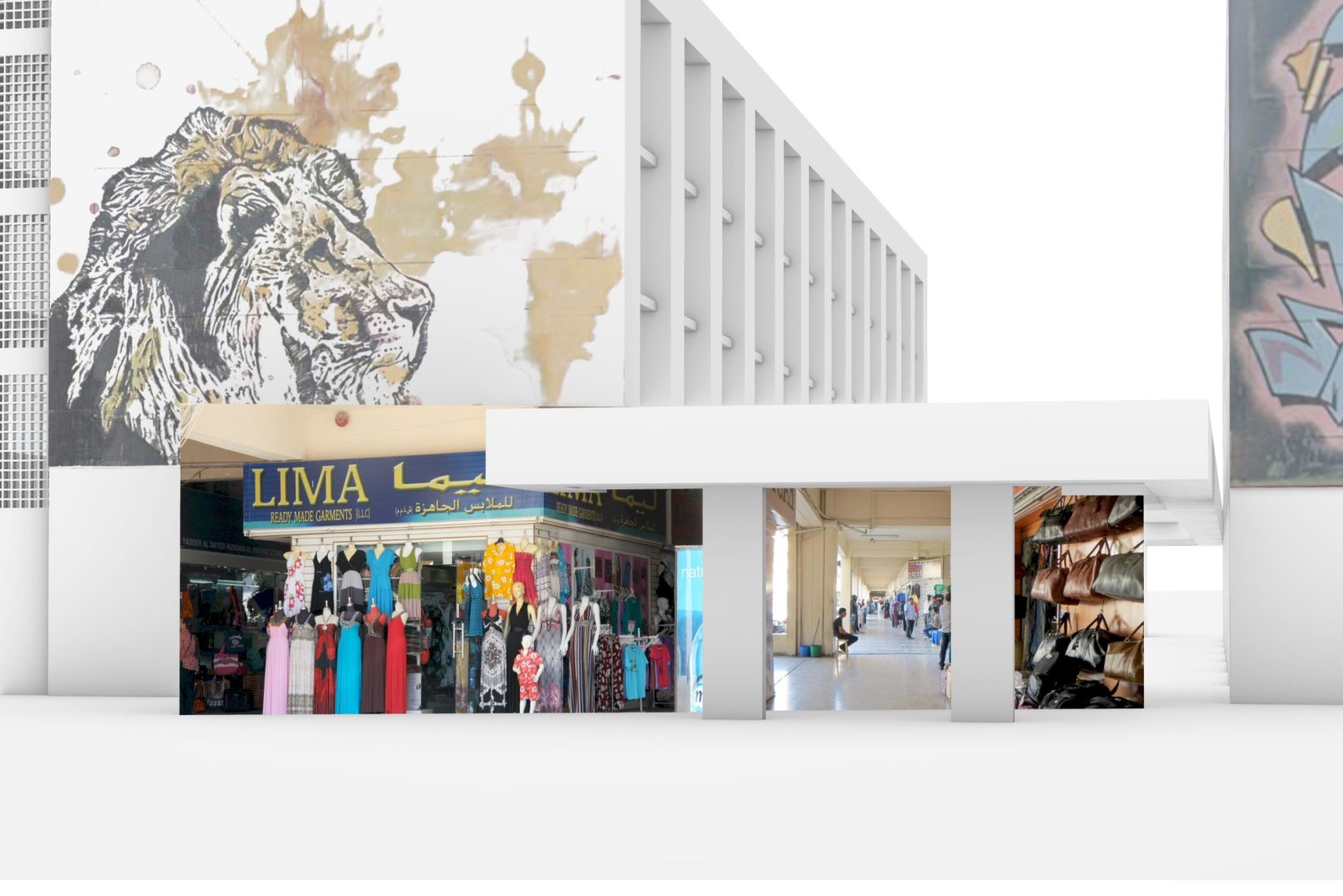

Dubai’s efforts to capitalise on its geographical location enabled it to climb the ladder to becoming one of the world’s most-known destinations for high-end fashion brands at the end of the twentieth century. Simultaneously, the Al Karama neighbourhood, where Karama Market is located less than four kilometres away from the mouth of the creek, continued to be home to immigrant communities who put down their roots in the country, promising prosperous commercial development decades ago.

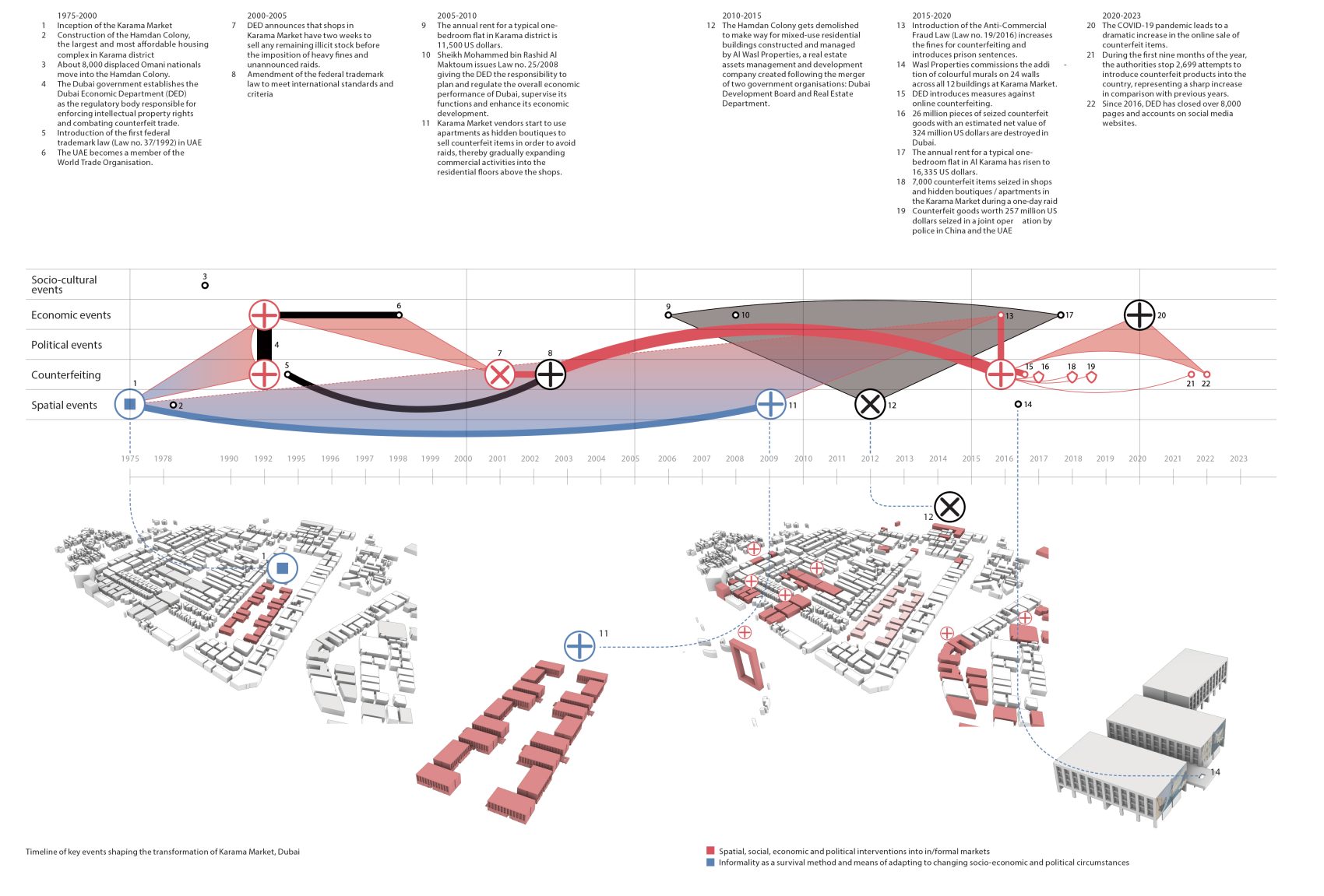

With the discovery of oil followed by the formation of the United Arab Emirates, investments in the city’s urban development flourished, making Dubai a world-class hub for commerce and tourism. The government’s ambitions to push forward the city’s economic momentum fuelled an expansion in its infrastructural development, leading its urban fabric to sprawl and to become home to high-end luxury brands from all over the world. With the rapidly growing tourism industry, its tax-free markets, and a geographic location that allows easy access to trade routes connecting to regions with low labour costs, lax intellectual property laws, and increasing demand for luxury products, a counterfeit economy emerged across the city

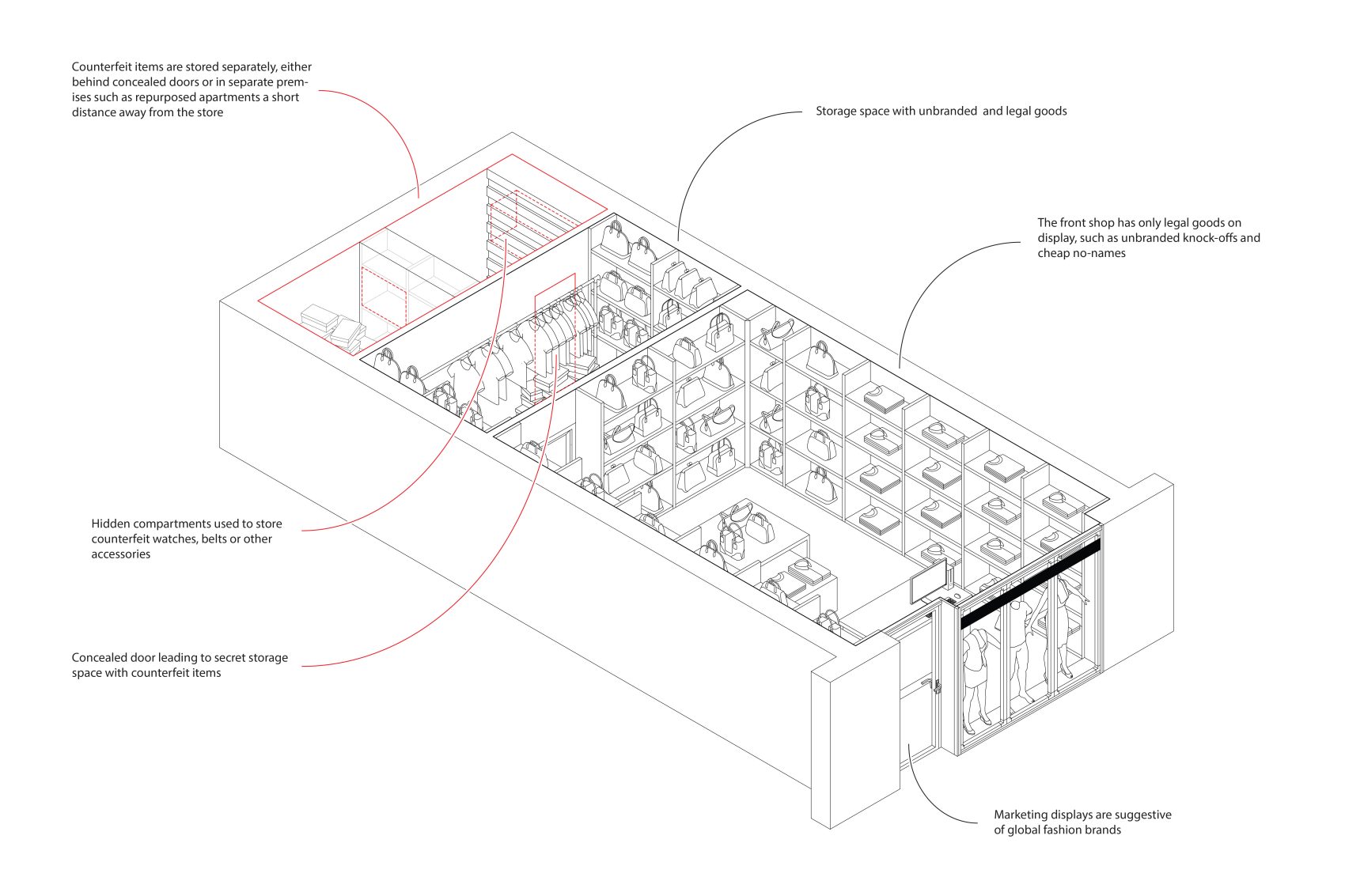

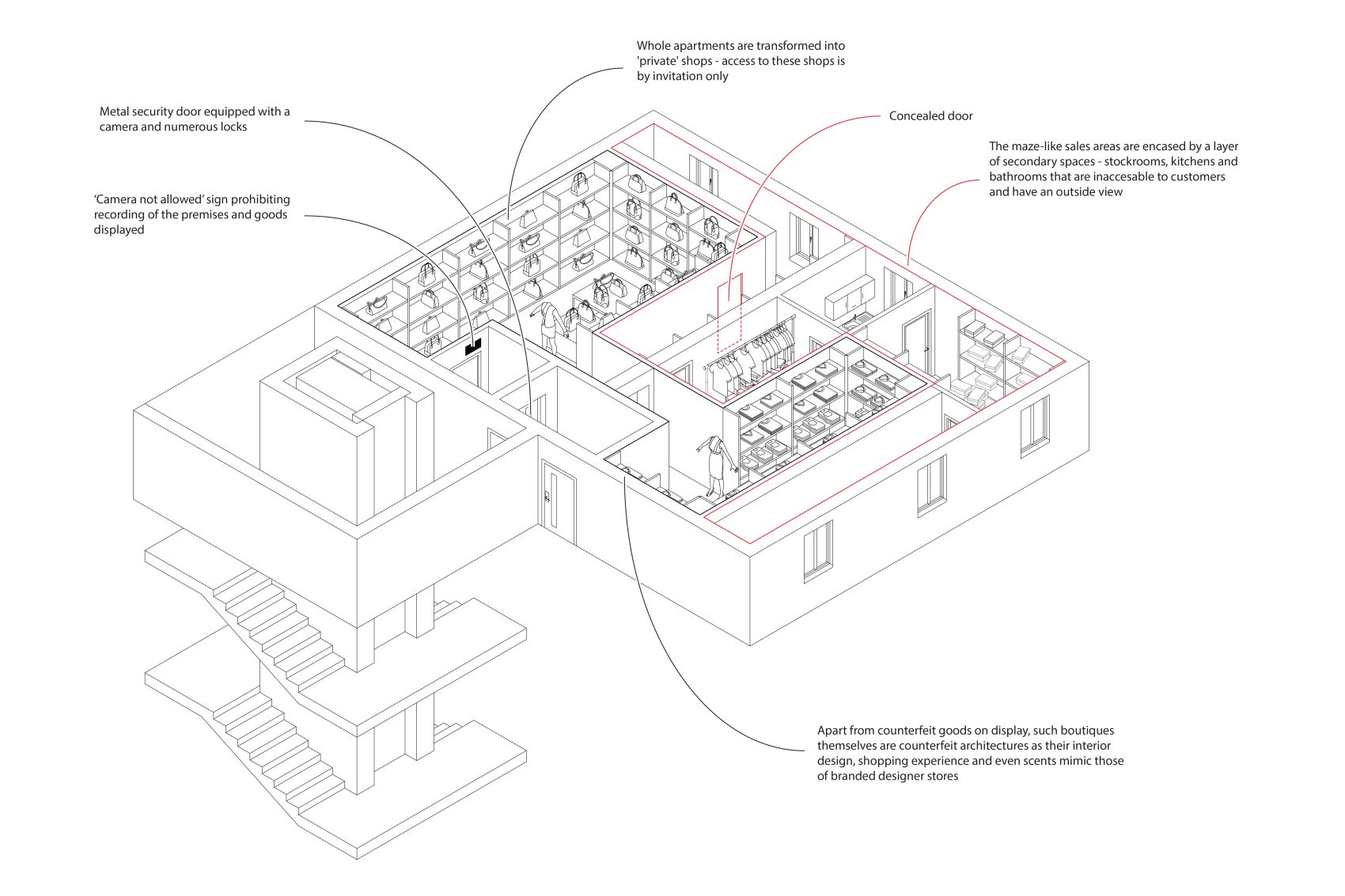

The Karama Market is one of the most locally known markets offering counterfeit goods to fashion enthusiasts wanting to associate with certain luxury brands without having to pay their prices. The Karama Market Complex is located at the heart of what is designated today as Old Dubai, a district that combines Dubai’s oldest residential and commercial neighbourhoods. The Karama Market’s location within the city strongly impacts its cultural, economic, and political development on multiple scales. This market becomes a node or interface, to trace how global, international, and national cultural, economic, and political dynamics continue to shape the evolution of informal economic activities. Despite efforts from the government to clamp down on counterfeit goods and protect intellectual property, the counterfeit market in Dubai continues to persist, albeit more confidentially and discreetly. The research suggests that the efforts to regulate the counterfeit trade are driving a redirection of energy towards clandestine trade exchange points and online platforms growing out of sight.

Location(s):Dubai, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

On-Site Collaborator:SAMAR HALLOUM

Visualisations:BILAL ALAMELOVRO KONCAR-GAMULINJOANNA ZABIELSKA

Photography: SAMAR HALLOUM

PETER MÖRTENBÖCK

HELGE MOOSHAMMER

Results of this case study were published in:

The Karama neighbourhood drew its strong transnational identity from its South Asian inhabitants, who infused it with the cultural interactions and customs that they brought and shared from their countries of origin. Despite living in the neighbourhood for decades, people continued to use the space in ways that activate their multiple heritages, characterised by complex intertwined webs of social and cultural interactions that later continued to support their informal trade relations.

Living within an immigrant community in Dubai gave the merchants access to resources, mutual support, and commercial information that would have otherwise been difficult to navigate. Through the strong trade connections with South Asia, merchants established networks that facilitated the supply of goods (e.g., garments, perfumes, and spices) shipped from South Asia and sold in the souks in Dubai’s old neighbourhoods. Clearly identified by the city’s residents as an immigrant neighbourhood, the retailers focused on offering daily necessities and affordable accommodation for the immigrant communities in Dubai.

In 1975, only four years after the establishment of the United Arab Emirates, the government constructed the Karama Complex covering 45,000 square meters. The complex was planned as a mixed-use development offering retail and residential rental spaces. It consists of six identical U-shaped buildings, each offering street-level retail spaces topped with 3 floors of apartments. Surrounding the Karama Market, other low-rise residential developments and commercial buildings populate the neighbourhood, many of which are currently owned and managed by the same development entity that runs the market.

The sprawling urban development along an axis parallel to Dubai’s coastline and the increased cost of living were forces that pushed retailers to shift their merchandise from affordable products targeting the neighbourhood’s residents toward products that attracted tourists. The trade in counterfeit products enables reaching prices per product that a product of similar quality and material but a different brand does not achieve. Goods appealing to tourists included a wide range of counterfeit products that later faced heightened restrictions and criminal fines.

Unlike informal markets that materialise as street markets or informal bazaars occupying parts of public city space, the research reveals that the informal trade within the Karama Market spills into the private sphere of residential apartments and, more recently, into a virtual network that is largely controlled and run by individuals living outside the country, but have networks to secure a delivery process within it. At this market, although some of the shops sell souvenirs, most sell fashion products that include shoes, handbags, sunglasses, and clothes. Wandering through the shops, one notices the emphasis on products that attempt to imitate luxury fashion brands with minor changes or intentional misspellings in the brand names, which maintain the appearance of goods that mirror luxury products.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Samar Halloum is an architect and researcher and holds a post-professional Masters Degree in Architecture (MArch II) from Yale University.