- Relocation

- FWF

- 2018-2023

- Incorporating Informality

Early morning at Roque Santeiro, Luanda, 2005

TOWARDS DE-CRIMINALISING THE ANGOLAN INFORMAL MARKET

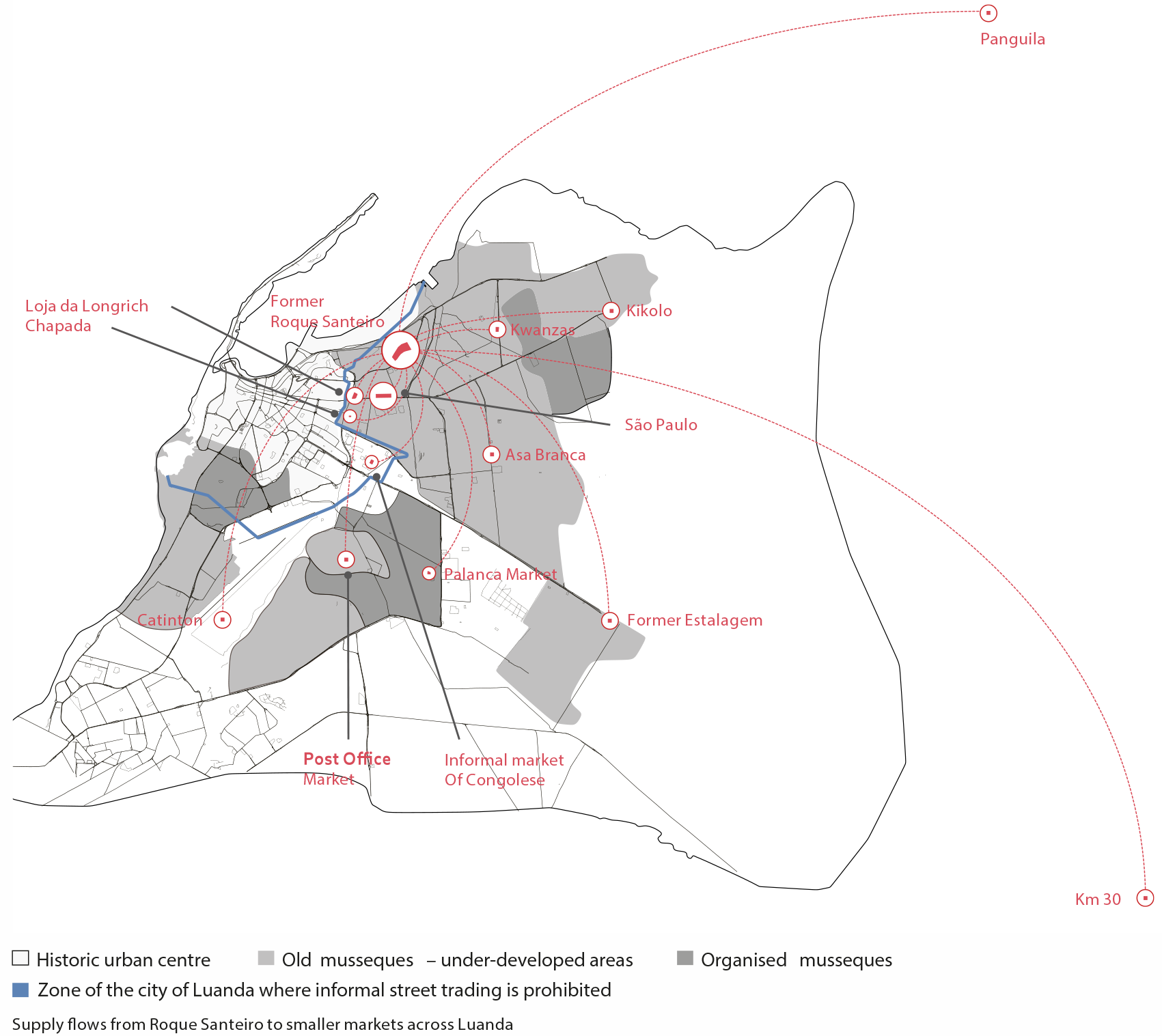

Angola’s informal economy grew out of the indigenous African markets of the colonial era. After independence in 1975, it took on an increasingly important role in supplying goods, services, and employment as the state-managed economy eroded under Cold-War conflict and weak management. Roque Santeiro was born in the war years and permitted to flourish without oversight and little government intervention. The ‘Roque,’ known as the ‘shopping centre for the poor,’ became the centre of Luanda’s economic life, functioning as a wholesale supplier to other district and neighbourhood informal markets. Roque Santeiro, the biggest and most important informal market in Angola and said to be the largest open-air market in Africa, was forcibly closed in 2010.

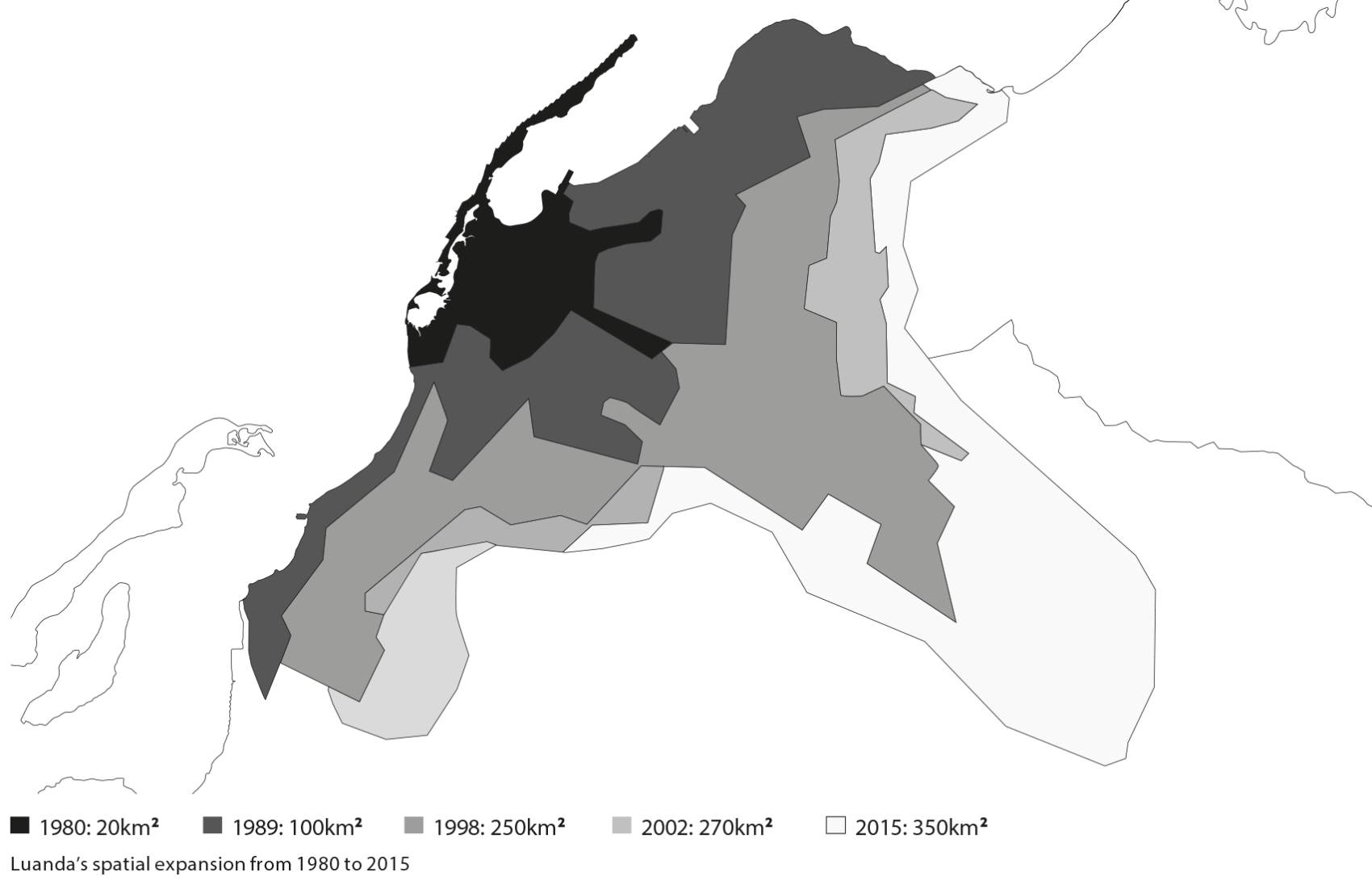

From as early as the 1980s, the parallel economy in Luanda began to prevail over the official one. There are many reasons for the pervasiveness of the informal economy; the economic exclusion of the African population has roots in the colonial era’s semi-fascist state policies; the chaotic transition to independence in 1975; the failure of the post-independence experiment in centralised socialist economics; the civil war that provoked massive internal displacement to Luanda’s informal musseque settlements and finally, the state monopoly of the petroleum-based formal sector economy. Amidst these shifts and crises, informal economies emerged as the primary system of day-to-day sustenance for Angolan citizens.

In 1986, official approval was given to create a market in the municipality of Sambizanga, overlooking the bay in the Bairro da Lixeira (formerly a rubbish dump). Some markets that operated in the northeast region of Luanda were to be relocated to the site. The market’s growth was spontaneous, beginning a few days after the installation of the first sellers when a sign with the name Roque Santeiro appeared. This name originated from the popular Brazilian telenovela Roque Santeiro, broadcast in 1985 by Televisão Popular de Angola. The television series was based on a banned play, O Berço do Herói by Dias Gomes, written in 1963. The Brazilian Military Government also banned the soap opera written in 1975. In Luanda, three markets: Roque Santeiro, Asa Branca and Beato Salú, were named after characters or locations in the soap opera.

Location(s): Luanda, ANGOLA

On-Site Collaborator:ALLAN CAIN

Visualisations: BILAL ALAMELOVRO KONCAR-GAMULINJOANNA ZABIELSKA

Photography: TIM HETHERINGTON for DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP

Results of this case study were published in:

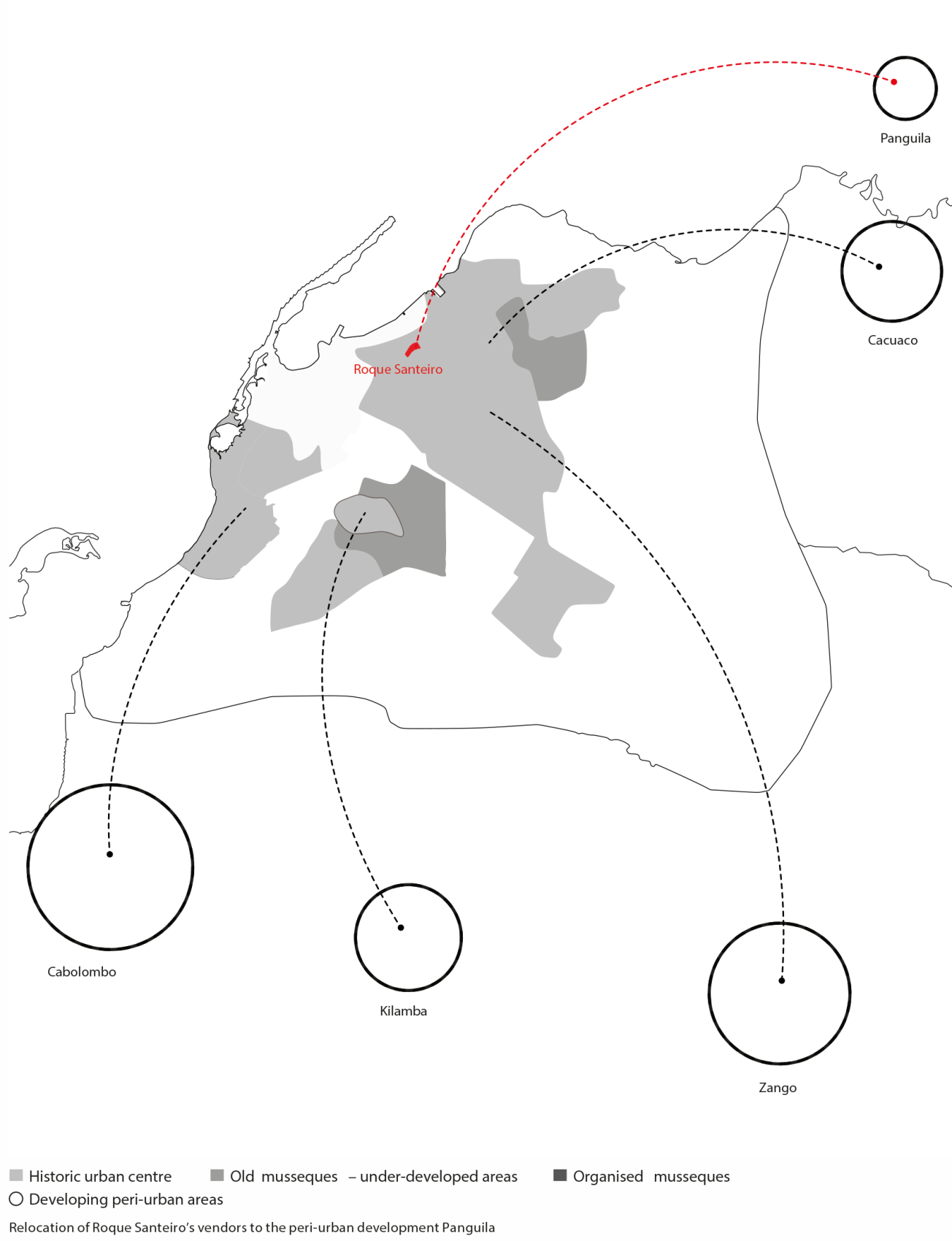

With the end of the civil war in 2002, the Angolan Government turned its attention to ‘cleaning up’ Luanda and turning it into a ‘modern’ world-class city. The chaotic and unsanitary informal markets and the surrounding slums were targeted for eradication. Informality had long been associated with criminality, and the state campaigned to restore ‘order’ to the post-war economy. The ‘Roque’ was the most famous victim. The market’s closure displaced thousands of traders and supported workers to seek alternative livelihoods in the sprawling suburbs of Luanda. Despite the Government’s campaign to formalise the economy, a decade after the closure of Roque Santeiro, the informal sector still provided 67 percent of urban employment. Angola has a higher rate of informal employment as a percentage of total employment (94.1 percent) than sub-Saharan Africa (89.2 percent) and Africa as a whole (85.8 percent).

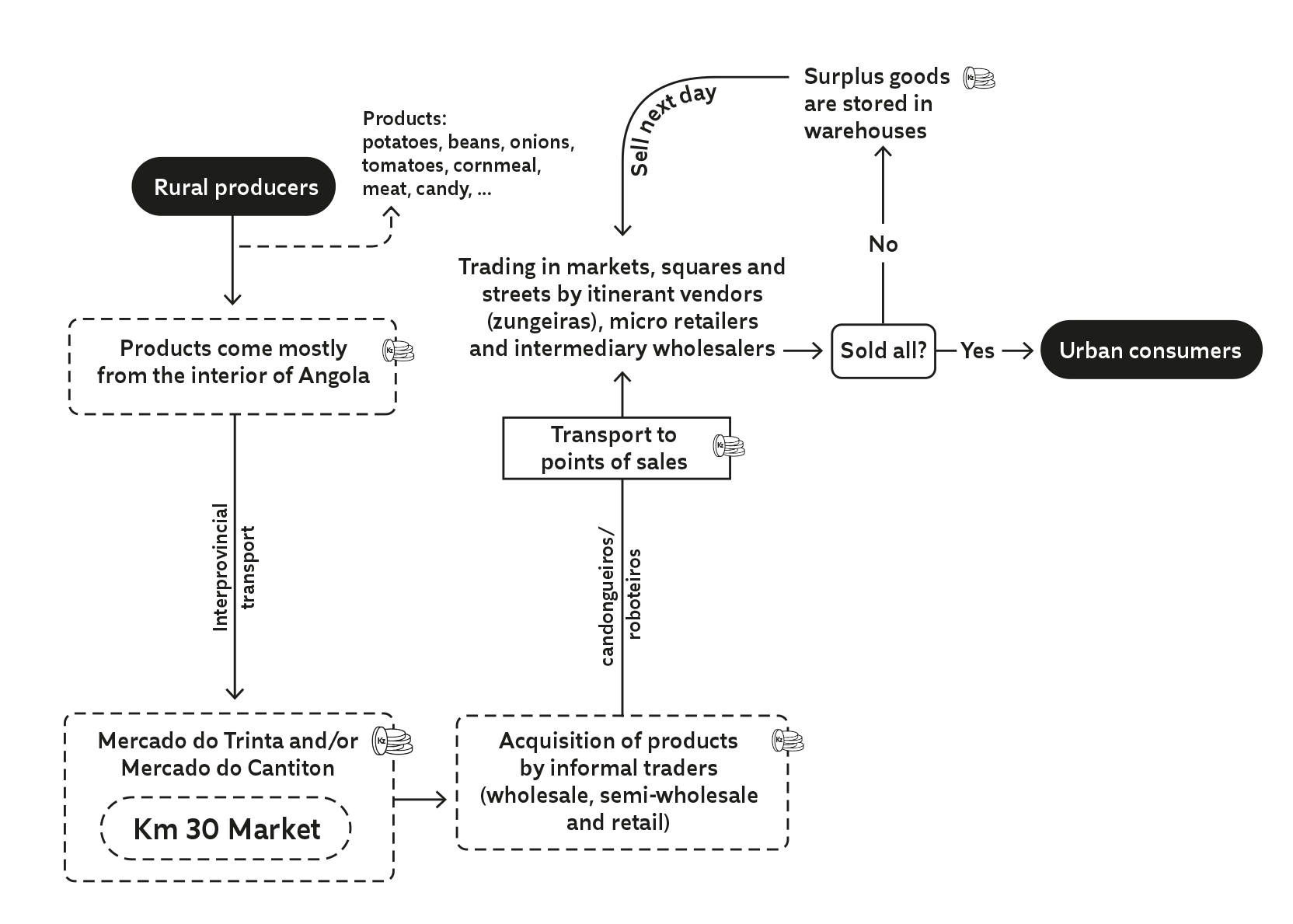

After the closure of Roque Santeiro, traders began to sell in the streets or from their homes. Despite the fact that these practices exist in opposition of policies imposed by the municipal government, the informal market does more than just employ two thirds of Angola’s urban families. The informal market provides Angolans with almost all of their basic needs, from housing, water, and transport, including getting to their informal jobs. Almost 90 percent of the land is occupied informally, leaving most families with precarious tenure, without land titles. Half of Luanda’s population is supplied by informal truckers who transport water from the nearby river, meeting a demand for water that the state cannot provide.

The post-war attempt at rapid and brutal modernisation by removing signs of the informal market, and its criminalisation and suppression over the years have failed. Recent evidence of the magnitude of this failure was made public by the state’s statistic bureau and studies commissioned by the National Bank.

Using satellite imagery and aerial photography, remote sensing has permitted the mapping and spatial analysis of informal markets on the urban district and neighbourhood levels. Participatory urban diagnostic tools have allowed the research team to capture the memories, stories and perspectives of the informal market entrepreneurs and street trades, gathered from former traders from Roque Santeiro, who had been displaced before or during the 2010 closure. All of this evidence proves the hypothesis of the importance of the informal economy in sustaining most Angolan citizens.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Allan Cain O.C. is a founding director of Development Workshop and has lived and worked in Africa since 1980.