- TRANS-NATIONALITY: LEGAL ARCHITECTURES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

7th Kilometre Market, Odessa, Ukraine, 2009 (photo: Kirill Golovchenko)

THE 7TH KM MARKET, ODESSA, UKRAINE: A CASE OF POST-SVOIET HETEROTOPIA

In the early 1990s, with the rush to capitalism, a new kind of commodity market began to appear across the vast territories of the former Soviet Union. Some of these markets have escalated into great transnational wholesale and retail trading points, attracting buyers and sellers from neighbouring countries as well as from China, the Middle East, Vietnam and Africa.

Ever expanding, these bustling markets have their own administration, police and security guards, and they have put in place bus services, parking areas, cafés, toilets, hotels, banks and medical facilities. The daily turnover can reach tens of millions of dollars.

What is interesting about these markets is that they are characteristically located in a grey zone just outside the city boundary and yet they exert a huge influence on the city’s regional clout, employment, immigration and transport links. The use of extraterritorial land raises constant conflict over taxation and the destination of the huge profits generated.

Here, we discuss the case of the Black Sea port city of Odessa in Ukraine, which has both old and famous central marketplaces (including one called ‘Privoz’ ) and a vast, externally located, container market called the ‘7th Kilometre’ or Sedmoi (‘seventh’ in Russian). The importance of spatiality to the latter market is indicated in its name, which designates its location seven kilometres out of town along the main road leading to the airport and onwards to Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria.

The market sprawls over 170 acres. For comparison, the largest shopping centre in the United States, the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, occupies only 96 acres (Myers 2006). But ‘7th Kilometre’, is nothing like a shopping mall. The market, expanding over open fields, is an entity that sees itself extending horizontally into areas called ‘sectors’, ‘stations’ and ‘fields. It has no pretensions to comfort, pleasure, ‘design’, or ‘atmosphere’. Instead, buyers must shoulder their way through narrow, dusty, open-air alleys between steel containers, opened at the front to reveal heaps of the cheapest goods. The ‘shops’ consist mainly of steel shipping containers stacked two high in rows long enough to be called ‘streets’. Many of these ‘streets’ are simply colour coded and names accordingly: there are green, blue, grey, white, etc. streets.

Sedmoi trades in clothes of every imaginable kind, shoes, furniture, electrical goods, domestic utensils, cleaning goods, sports equipment, videos, music, jewellery, cosmetics, leather goods, ceramics, spare parts for cars and other machinery, do-it-yourself and home decoration goods, souvenirs, …and practically anything transportable that can be traded (though relatively few food or animal products are sold there). Legal, transport and employment services are also big business. The market has its own website with a detailed map and news update (http://www.7km.net), administrative building, and feared police and guards.

Location(s):Odessa, UKRAINE

On-Site Collaborator:VERA SKVIRSKAJACAROLINE HUMPHREY

Photography: KIRILL GOLOVCHENKO (2006-09)

VERA SKVIRSKAJA (2011)

Results of this case study were published in:

Business starts early in the morning at around 4 o’clock; the really illegal transactions, e.g. guns and drugs, are rumoured to take place before this, ‘at night’ (Polese 2007). After the market closes, around 3 in the afternoon, when all the buses and cars have departed, nothing remains but a desolate landscape of battered containers, a few box-like concrete shops with steel shutters, and plastic bags blowing in the wind. The market becomes animated again when exclusively wholesale trade starts up late in the evening and continues through the night.

Founded in 1989, as perestroika reforms were getting underway, Sedmoi claims to be the largest market in Europe. It has roughly 16,000 traders and a staff of 1,200 (mostly guards and janitors), making it the region’s largest employer. Daily sales were quoted at USD 20 million in 2004 and must have grown since then. An estimated 150,000 customers arrive each day, coming not only from all over Ukraine but also from a radius of up to 300 miles into Russia and other East European countries. The practice is to make an overnight daytrip of it, with most customers coming to buy ‘wholesale’ (optom) in order to re-sell in small towns and villages. Setting out one morning by bus, one can reach Sedmoi by nightfall, catch the early morning sales, grab a bite to eat, pile back into the bus or trains groaning under goods, and be home by nightfall the next day. Some villages in the poverty-struck Ukrainian countryside have their own depots, called ‘Our Sedmoi’, which middlemen traders (perekupshchiki) periodically replenish from the main Odessa site.

Locals and the mass media often refer to Sedmoi as a ‘state within a state’. If it is a ‘state within a state’, it is one that is surprisingly easy to enter. The market is not surrounded by a wall or protected by anything beyond a fence and it asks no questions about the nationality, visa or asylum status of people coming in either as traders or purchasers. However, the Ukrainian state boundaries are another matter. The purchasing hordes do face certain slightly tricky moments when they return across international frontiers with their great bundles, for protectionist policies are still the preferred way of encouraging local business. In this situation large firms have to pay duties, but for the crowds of individual purchasers, as Polese observed on the train running between Odessa and Chisinau in Romania (2007: 9), trade and smuggling are essentially indistinguishable. Well-established routines with the border-guards ensure that the goods pass through and the guards are satisfied.

Setting up as a trader at Sedmoi avoids taxes, duties and licenses. All one needs is connections and/or money. The containers may be bought as ‘real-estate’ – their price shot up from around USD 1,000 in the late 1990s to $240-250,000 in 2007 – and then franchised out to employees. These employee managers then hire sellers (realizatory) on a day-to-day basis to retail the owner’s goods. One seller told us she received 3% of the profit on everything she sells and returns the items she does not sell. It is quite easy to obtain such dead-end work. The other model is to rent a container from a boss in order to set up one’s own separate trading business. In this case, the renter is responsible for obtaining the goods as well as selling them. This is a riskier path – huge loses can be made, as well as great profits. Now certain payments are made by all owners/bosses to the central administration of the market, and an uncertainty hangs over whether these payments should be conceptualised as tax or rent. But what is clear is that the normal taxes, imports, town rates, licenses, etc. of the surrounding Ukrainian state are almost entirely in abeyance within Sedmoi. It is up to the individual traders to comply (or not) with such regulations. The Deputy Director of Sedmoi has been quoted as saying that the market’s owners pay roughly $11 million per year in federal and local taxes – a contribution which is disputed by the Odessan city authorities – but as for the income and other taxes and customs duties of the vast army of traders, that is not his business. “We never tried to control it,” he said. “We are not the tax authorities” (Myers 2006). Evidently, this is the main reason for the low prices to be found at Sedmoi.

THE MARKET AS A HETEROTOPIA

In relation to the city, which is also commercialised, such a market is like its bad boy alter-ego. It can be seen as a heterotopia, to use Foucault’s expression. Such places, he suggests, have a mirror-like relation to us. They are ‘real places… that are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which … all the other real sites that can be found within the culture are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted’ (Foucault 1986: 24). We shall take a hint from Foucault’s description of one kind of heterotopia to argue that these new commercial structures are the brute reality of socio-economic life. Foucault writes that heterotopias ‘have a function in relation to all the space that remains’, and the role of certain of them ‘is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory (perhaps that is the role that was played by those famous brothels of which we are now deprived)’ (1986: 27). It can be argued along these lines, that since the rock-bottom, indecent intensity of money-making in the 7th Kilometre underpins the economy of the whole of southern Ukraine, perhaps even that of the state itself, it is the polite boutiques and significantly empty marble-and-chrome malls of the city centre that are the illusion. Even in the Privoz market in central Odessa, with its banter of sellers of fish and cheeses, bric-a-brac and home embroidery – in the sense that the iron structures of the 7th Kilometre are coming to take over everywhere.

Odessa – and perhaps any city – always needs and creates for itself (or allows to be created) a notional space of ‘outside’, and this, as Foucault argues, is intrinsically heterogeneous (1986: 25-6). It does not have just one function. Raw and single-minded as the pursuit of money at 7th Kilometre is, this commodity market also evokes various imaginaries, has its own cross-cut of time different from that in the city, welcomes foreign people who are excluded from Ukrainian social life, and opens out into vistas of far-off sources and destinations. Both purchasers and traders are a motley crowd, many of whom do not have Ukrainian citizenship. The purchasers mostly come from neighbouring regions and countries. Some of the traders are local, but they also include increasing numbers of Chinese, Turks, Russians, Vietnamese, Armenians, Georgians, Gypsies, Central Asians, and Africans from several different countries. The market has its own organisation of time, with its Muslim day of rest (Friday) in a Christian country.

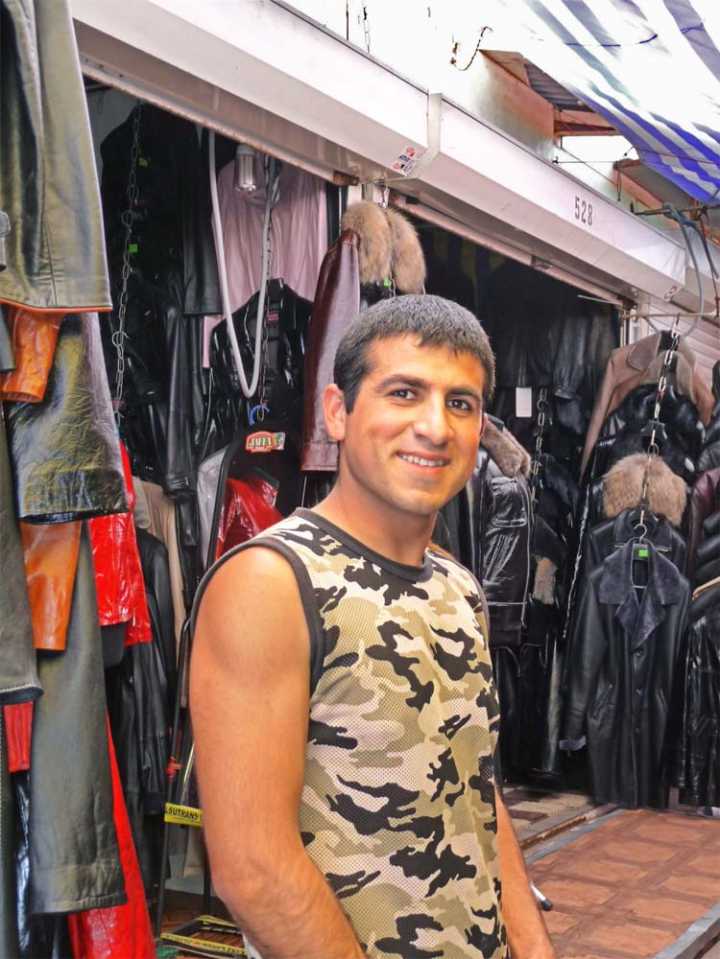

There are ethnic neighbourhoods and enclaves at Sedmoi. This happens because each type of commodity is allocated its own trading streets, and trade in these commodities has become the preserve of particular nationalities (giving the market a bazaar-like quality). Thus, Ukrainians, Bulgarians and Russians sell cleaning items (washing powder, soap, pails, dishcloths, etc.) as well as perfumery and cosmetics; Chinese sells jeans; Turks specialise in leather clothing; Africans sell trainers; Afghans trade in footwear and electrical goods, and so on. The money-changers are Vietnamese –discreetly giving the appearance of ‘someone just waiting’, they lurk in the alleyways.

With no need for a container, they move at cross-roads, jostled by food vendors pushing their home-made carts and yelling their multi-cultural wares – hot coffee, roasted peanuts, vareniki, hachipuri, lavash, lyulya kebab, etc. (1). Now that the ethnic division of labour has stabilised, their physical appearance (“Vietnamese”) is enough to identify who will change money. The co-responsibility of any Vietnamese for any such monetary transaction guarantees that customers will get a ‘fair’ exchange rate (Prigarin 2007n.d.). Some changes in ethnic enclaves on the market have also taken place over time: if in the 1990s, Turks were the main sellers of leather goods from Turkey, this trade has been partially overtaken by locals, while many successful Turkish traders moved into new businesses in the city proper. Money made on the 7th km is said to have financed some popular Turkish restaurants and night clubs in Odessa.

The important point is that all non-local traders of non-Slav appearance are liable to racist attacks in the city. Several Vietnamese currency changers are rumoured to have been murdered on their way to and from the market. The locals have a repertoire of insulting terms: ‘Negry’ (from Africa), ‘Cherniye(Blacks, i.e. Indians, Afghans, Gypsies, and from the Caucasus), ‘Churki’ (from Central Asia), ‘Zverki’ (‘little animals’, small groups of foreign-appearing people). The expression ‘Non-Russian’ (Ne Russkii) has become a joking term of abuse for anyone who seems different, not one of us, and it is used by all kinds of Russian-speaking people, even Arabs. In other words, ‘we’ are Russians by default (2). In this environment, ‘Blacks’ like the Afghans are especially vulnerable to attacks. The Afghan traders mostly rent apartments in Odessa rather than sleep at the market. But they only travel to and from the city in small convoys for safety. Their social life in the city is mainly with one another, but on the market various non-Afghani traders are friends. For many local Russian and Ukrainian traders, the 7th km is the only place where close repeated contacts with ‘Non-Russians’, e.g. Chinese, Arabs, Afghanis, are feasible and acceptable.

So Sedmoi really is like a world on the other side of the mirror. To its denizens it is a place of security, mini-power, and opportunities not found in the city. Here reviled alien outcasts can feel at home; the unemployed can find work; here the fresh-faced Ukrainian seller has someone else (‘the master’) playing cards and drinking brandy in the back of the container; here a precious space has been created where an entrepreneurial person can make money independently of the state. Alternatively, from the perspective of upright state employees of Odessa, this market is nothing but the dump where the detritus of world petty capitalism gets blown. Perhaps it is not surprising then that Sedmoi is an occulted, phantasmic place in some ways. Unlike the kind of sites of supernatural danger analysed by Mary Douglas (i.e. located in the zones of indistinction where different classifications overlap), the heightened occult awareness of the people at Sedmoi is created by its separateness, its irreducibility to either the space or the time of the city.

Sedmoi is a separate place. But it is one that the city is trying to take over. In autumn 2007 a power struggle was (and still is) raging. The city is battling in the courts to claim part of the market in ownership and to retrieve 500 million griven (100 million dollars) as compensation for unpaid dues. The traders know their profits are at stake. On the 29th September 2007 they held a mass protest meeting. They agreed to picket the Odessa Town Soviet and to send a petition with 11,000 signatures to the municipal authorities. More recently, they agreed to prepare a referendum for a vote of no confidence in the Mayor, Eduard Gurevits, whom they held personally responsible for the court case (3).

It is already the case that Sedmoi has become such a super-desirable alternative and subversive power that it can be seen as the mercantile heterotopia not just for Odessa city but for the whole of Ukraine. During fieldwork in 2007 we asked a Russian trader at Sedmoi, ‘Who is the master (khozyain) of the market’? Without hesitation she replied, ‘The President of course.’ Taken aback, we could not at first understand that she meant the president of Ukraine. Apparently, according to her, several proposals had been made to move the 7th Kilometre to Kiev, the capital of the country. The move had been blocked by opposition from the Odessan authorities, who argued that thousands of jobs would be lost and the whole south of the country thrown into economic ruin. Next, Timoshenko, when she briefly took power, threatened to close the market down (for violation of tax regulations). Finally, President Yushchenko paid a visit to the market. Some arrangement was made. Now, the trader assured us, the president made regular visits every two months and pocketed USD $20 million each time. The reality of such a deal was of course shrouded in mystery, though the media provide hints.

The mystery and lack of transparency is of the essence of this kind of market space. For many people realize, and the traders certainly know, that its glorious profitability depends on the market not being regularized, transparent, fully taxed, or nationalized. As of 2007, even the president seemed to have abandoned the idea of subjecting Sedmoi to his power; he could only live off it. And as for Odessa city with its attempt to drain off a reliable stream of funds, people talked only of the looming combat. With the economic crisis of 2008-9, the wonderful profitability of Sedmoi began to melt away. With containers locked, empty, or removed altogether, many traders were having to find alternative ways of earning a living.

The idea of the ‘heterotopia’ encapsulates well the multiplicity of ways that such a transnational market challenges, yet links into, the (relatively) legal mainstream economy, culture and society. It has its own spatial lay-out and architecture – a lateral, cell-like, modular, spreading, aesthetic that contrasts with the vertical ambitions of the city centre. The market’s internal policing provides physical security and the possibility of home-like sociality for the various strands of multi-national trade networks; and this again contrasts with the xenophobia that seems to have arisen in Odessa recently. Unlike the grey and anonymous ‘non-places’ that proliferate at Western sites of connectivity (all those airport concourses, supermarket aisles, long-distance bus stations, trading floors or internet cafés, Augé 1996), the container market has become a place of intense social interaction.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Augé, Marc 1995 Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity.

Translated by John Howe. London: Verso.

Foucault, Michel 1986 ‘Of other spaces,’ Diacritics, Spring 1986, 22-27.

Myers, Stephen 2006 ‘From Soviet-era flea market to a giant makeshift mall,’ New York Times, May 19.

Polese, Abel 2007 n.d. ‘Border crossing as a strategy of daily survival: the Odessa-Chisinau elektrichka’ (unpublished MSS).

Prigarin, Aleksandr 2007 n.d. ‘Rynok “7 kilometr”: torgovaya subkul’tura v sovremennoi Odesse’ (unpublished MSS).

(1) These are Ukrainian, Central Asian and Georgian foods. See ‘Petro’s Jotter, Observations of Post-or Ukraine’, at the Seventh Kilometer website.

(2) This may seem strange in a Ukrainian city. Odessa, however, has always been a Russian-speaking town. Possibly, the term ‘Ne Russkii’ is a local Odessan expression.

(3) Official site of Promrynok 7-oi Kilometr, news, 01.10.2007.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Vera SkvirskajaDepartment of AnthropologyUniversity of Copenhagen, Denmark

Caroline HumphreyKing’s CollegeUniversity of Cambridge, UK