- LAND USE: TRANSIENT ECOLOGIES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

CASE STUDY: CARRICK-ON-SHANNON CAR BOOT SALE

Signifying will

CAR BOOT CONCEPTION

Car boot sales are traditionally marginal sites of social interaction and often the diverse groups and individuals who compose the community are not in strong positions to exercise political agency within mainstream society.

The car boot sale is a vital cultural event in terms of social relations, alternative economies of exchange, value judgements, conservation and preservation through the circulation of objects and their affects.

The car boot sale can be imagined as:

– A contact zone for gathering, collating, re-presenting and disseminating people, objects, relations and knowledge.

– A focal point through which various levels of information and experience are received and transmitted between groups and individuals.

– A collaborative zone where economies based on exchange and giving produce effective means for revealing and retrieving history, memory and meaning pertinent to constitutive publics.

– An archive liberated from its historical incarceration in the media and social and political institutions; to “…project the social imagination into sites of testimony” (Derrida) and create mobilised discursive spaces.

– An archive also, in the sense of an accumulation of the historical residue of cultural artifacts; collected, collated and made accessible and open to public investigation.

Location(s): Carrick-On-Shannon, IRELAND On-Site Collaborator:Adam Burthom

Photography: Adam Burthom

PRIVATE PUBLIC SPACE

In the case of Carrick-on-Shannon car boot sale, a space has been opened up/carved out of the contested and conflicted social and geographical terrain.

One day a week a petrol station forecourt is given over to ‘public’ use.

Through negotiation, agreement and collaboration between landlord and tenant, property and people, a beneficial partnership involving mutual trust and patronage emerges: A contrived and constructed occupation under the terms of a contract that adapts to changing circumstances as they occur. The result is effectively, a collective purchase of space and time that ‘acts’ as a ‘commonage’ for social gathering.

That the space within which a functioning ‘demo-s-phere’ can operate only exists through financial arrangement with a proprietor reveals the state of human relations with each other and the land. The ancient right once held by the people to have access to ‘common land’ for the purpose of gathering together and going about daily business unhindered, no longer exists. All land is under ‘legal’ possession either by private or state interests. Therefore a privately rented temporary space provides a legitimate and secure refuge for public occupation.

The car boot community buys a time and a space where economic relations, news and activism can travel, creating a zone where the rules of the dominant social factions are suspended (or at least the contours of the social landscape are altered, shifted and blended in search of a different balance).

Unfettered, unimpeded and to an extent ‘beyond’ the law; the natural function, instinct and desire of the ‘social human creature’ to congregate in order to communicate, exchange, share and support finds a way to manifest. It is in this sense that the car boot sale could be conceived of as a potential threat (to an established order).

THE OPEN BAZAAR & HUMAN RELATIONS

The bazaar is the hub of social and economic relations outside of consent and control. Value and worth operate on a different register. A fuller, more accurate reflection of the shifting composition of the social fabric is presented. Multiple layers of race, gender, age, spirituality, political view, education, family, desires and trajectories converge outside of their ghettoised existences.

The community assembles as a ‘dis-unity’ (a uni-diversity), manifesting a common arena, form and foundation for social, political and cultural survival. An economy of people, objects and their relations: a parallel public consciousness.

Through the principle of the bazaar, conceived of as a model through which the means and methods for producing a harmonious state of co-existence are constantly evolving, individuals and communities find their territorial limits, settle their differences and seal their bonds, in open and visible inter-relations.

By virtue of its openness and visibility the common space presents and challenges perceptions emanating from a society where public opinion ferments behind closed doors, informed by means of institutionally filtered broadcast techniques.

Entrenched beliefs are questioned through contact with the ‘Other’. Cultural differences point to alternative possibilities and hybrid configurations: Evidence of life from beyond the screen of public pre- and mis- conception challenges media stereotyping and mis-information.

PUNTERS

The ‘transient’ enter in and pass through, in contrast to the seemingly permanent and familiar for whom the sale is the weekly point of contact with distant neighbours.

Being on the side of the busy main road between the East and the West coasts of Ireland, there are passers-by on their way to other destinations but who stop to satisfy their curiosity. Attracted by the opportunity to pick up a bargain, find some interesting, useful or sought after object for a good price.

Some have an irresistible compulsion to buy something no matter what it is or whether it will lie idle in a shed long afterwards. One often hears a person say that they have no need for the thing they are buying but that they must come away with something to bring home. The desire is to engage in the search, discovery and price negotiation and leave as if having caught some game, or won a prize, reward or trophy. Some see their buying as a form of financial support, using their resources to maintain the economic flow of the community and perpetuate the car boot sale’s existence.

Dealers scour the stalls looking for objects to lift out of the boot sale level of trade and transfer to shop or auction house level, where higher prices can be realised. They are the gatekeepers to a market that is inaccessible directly to marginal communities. Their advantage is knowledge and network connections.

PLAYERS

Stall holders have many motivations to stand out in all weathers, week in week out: From clearing out household clutter to moving merchandise for profit; dealing in that which is unwanted to that which is dearly loved, a special interest or passion; or for the pleasure of handling beautiful or desirable objects. Some stalls sell goods to raise money for charities while most are simply trying to raise some extra cash supplement. For others it is the main source of income revenue and only one stop of many at other sales and markets made during the week. The boot sale also offers the opportunity to promote services, skills, trades and knowledge.

Regular stall holders form a core community composed of market traders, travellers, enthusiasts and supporters, and around this nucleus a transient community of passing traders gathers. Everyone is punter and player, buyer and seller participating in the complex world of boot sale relations.

The people who attend the car boot sale live a precarious existence, trading at the bottom of the economic pyramid where the status quo, the thin membrane of social order, can be disrupted by a simple act of legislation or policy intervention. At any particular moment the level of trade, the buying power of visitors, the composition of goods on offer, the mood of the people, observation of audio and visual codes, signs and socio-cultural identifiers make the event a significant barometer of the effects of current local/global situations.

BOOT SALE MUSEUM

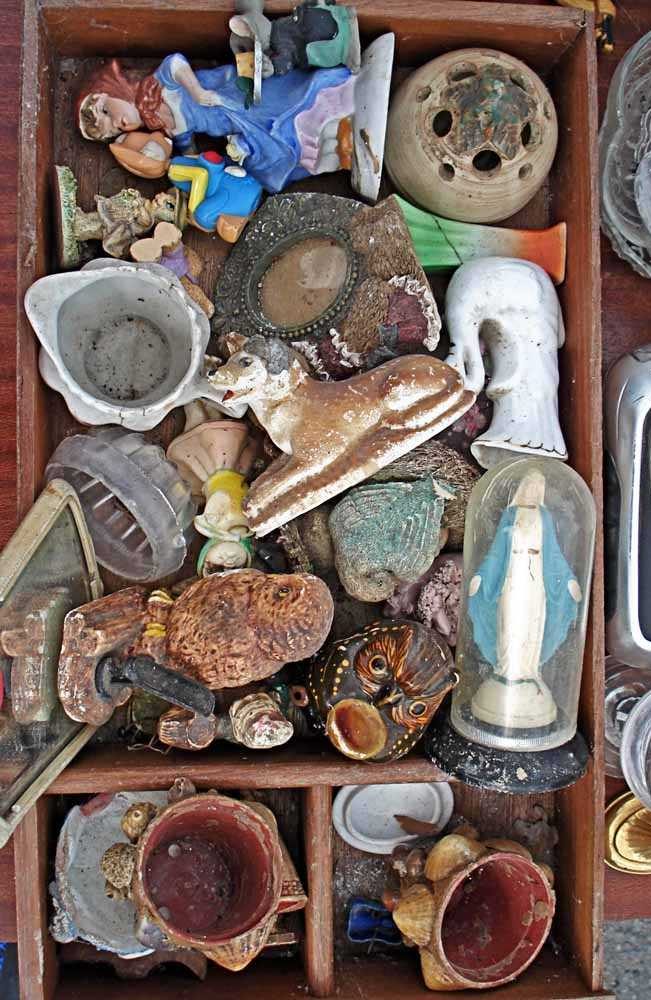

The car boot sale functions as a museum in motion employing voluntary (at times unwitting) public ownership/stewardship of an archive built from what is actually relevant and tangible to its custodians.

Memory and meaning produced by means of objects and testimonies manifest a form of signification. Here the ‘marginal’ stage a repossession of personal and shared histories running parallel to mainstream discourses.

Things that hold their value will continue to circulate over time but the nature of value that maintains circulation varies; it can relate to the use value, monetary value, beauty as a value, curiosity, obsolescence, historical interest or importance etc. Someone may buy an object and then return it to the network at a later occasion when interest has waned or usefulness has ceased.

Some objects remain functional whilst others whose function becomes outdated in the light of technological innovation, serve as memory carriers, ‘touchstones’ tangibly conveying into the present, a past ingenuity and social order. Serving to reveal the state of the present placed in contrast/comparison to recollection (what is not now the case) and imaginatively creating a potentiality for time to come.

IN CONCLUSION

The car boot sale as a ‘free’ space remains a mirage, an illusion: A contrived utopian vision and model always constituted in terms of financial agreements and conditions, rules and regulations, manners and etiquette. Yet there is potential here for all these factors to be acknowledged, managed and refined as part of an evolving public consciousness directed towards a future horizon that is determined by the ‘Will of the People’.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Adam Burthom