- Marga van Mechelen

- University of Amsterdam

SURVIVAL KITS: Artistic Responses to Globalization

New Babylon

Speaking about Survival Kits and Globalization, the first thing that comes to mind is a picture of an age of global unrest, of political troubles, of wars followed by forced migration, and ecological disasters, which force people out of their homes. This raises the question: what do people need to survive it all? Obviously, both literally and figuratively speaking, there is a need for shelters, and survival kits can respond to this need for protection – or they can symbolize it. The survival kits addressed here are at times products that aid survival in severe circumstances, but first and foremost, they entail a combination of physical objects and symbolic representations of the state of the world. All of them are designed by artists, in the broadest sense of the word. These kits are connected to a worldview, no matter how divergent these worldviews may be. In spite of all their differences, both the titles ‘Gimme Shelter’ and ‘Survival Kits’ do not suggest an optimistic view of the globalized world. Both color our notion of globalization without allowing much room for a more optimistic approach.

When I presented a paper at an Art History conference in Manchester in the spring of 2009, in which I discussed many of the examples I will discuss here too, the title was: New Babylon or a virtual house for the art world citizen.(1) It suggested something different, namely, the creation of living conditions for a new multilingual or multicultural world. New Babylon refers to a project by the Dutch Cobra artist Constant Nieuwenhuys, who worked on it for several decades, after the Cobra group which he was a member of, was suspended. Nieuwenhuys was closely involved with the foundation of the Situationist movement in the year 1958, and is most noted for his contribution to unitary urbanism, and for this New Babylon project, which includes a series of models, collages, writings about urban development and social interaction as he could imagine them for the future. Though decades before the development of the World Wide Web, he already thought in terms of virtual networks. But he was also preoccupied with new ways of living and transportation that protected the citizens against the congestion of modern cities. His alternative was neither the old alternative for a metropolis, namely that of a garden city, nor a futuristic design, popular amongst some of the historical avant-garde movements. However, ingredients of both models can be found in his project. Years later, both aspects of the New Babylon project served as inspiration for widely divergent architectural bureaus or groups of architects such as Archigram, Superstudio, Archizoom, and later the Office of Metropolitan Architecture, as well as architects who privilege ecological building principles. If the topic ‘Gimme Shelter’ and ‘Survival Kits’ has a negative connotation, the concept of New Babylon has a more positive connotation, that is, granted that the word ‘virtual’ does not give one the shivers, or there is any other objection to the type of urban design Constant Nieuwenhuys had in mind. New Babylon was not built for anxious people, but for those who love freedom and the unpredictable; not for people who work under safe conditions from nine to five, but for people who think differently, and more creatively about work and free time. The word ‘Babylon’ reminds us of an idea and ideal place where all cultures can meet, where cultural differences can be overcome. However, it simultaneously points to its failure, due to the difficulty of communicating with each other. New Babylon gave this utopian idea a second chance.

1989

In general, the effects of globalization evoke different emotions and evaluations, and this also applies to artists and curators. Since the nineties, however, the relation between artists and curators has been drawing closer than ever, to the extent that one can speak of blurring the line between them. Nevertheless, it is my impression that artists and curators respond differently when it comes to globalization. Of course, there are numerous artists who are willing to participate in Biennales engaged with topics related to the effects of globalization, but still this is insufficient to convince me of the similarity in their approach. Curators seem more interested in the general phenomena of globalization, such as migration, itinerancy and Diaspora. Most artists, however, seem to be more involved with how globalization directly effects local situations and private circumstances, or they leap at the opportunity to explore new ways of global communication. Before going into detail and discussing the ‘survival kits’ of artists and designers, I would like to have a look at curatorial practices since the early nineties, specifically since the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, which was commemorated this year.

The year 1989 was remarkable, and not only due to the fall of the Berlin wall. As with the year 1968, it can be considered the starting point of a new era. 1989 is the year in which several publications appeared which explicitly reflect on the broader developments of globalization. It is the year in which Solidarnosc won the elections in Poland, Milosevic came to power in Serbija, Ceausescu was executed – all factors which changed the relation between Eastern Europe and the West (i.e. Europa and the USA). It was the year in which De Klerk won the election in South Africa, and when a demonstration in China ended in a catastrophe. The erection of the Haus der Kulturen in Berlin and the exhibition of Magiciens de la terre, are historical events that signal the way the world opened itself. If we focus on publications, our attention is drawn to references that diagnose the state of the world after the end of the Cold War, or the effects of globalization in retrospect, as for instance, in very different ways, in Fukuyama’s essay and later book The End of History, Julia Kristeva’s Étrangers à nous meme, and Slavoj Zizek’s The Sublime Object of Ideology. Though 1989 is not the starting point of an outburst of biennales, soon after, one became aware that the art world indeed had become a global art world. For this reason, the eyes of the art world were drawn to the first Documenta after 1989, the one curated by Jan Hoet in the year 1992, who proclaimed to start from point Zero. He travelled around the world to scout new interesting artists during the three years of preparation. The expectations were high, but the results rather disappointing. Much more important for the reflection on the globalization of art were the Documentas that followed.

All three of the Documentas discussed here point to the idea of the Documenta as an instrument for understanding the world of art, and not only the Western world as it had been before. The Documenta became an exhibition that simultaneously mediates the state of this world, and dreams about its salvation. These are not my words – in my ears they sound a bit exaggerated – but words used in the media.(2) It also left a mark of the world of today: a complex and rather bad world. So there was not much enthusiasm for the effects of globalization, but still a certain trust in the possibilities of the world of art. These Documentas purportedly presented art as a giant network. But how did each of them achieve this? In the case of Documenta X, curated by Catherine David, not only by means of the exposition, but mainly in the catalogue which included many theoretical contributions on the globalization of the art world. This was supplemented by a so called parcours (itinerary) through the town from the railway station to other venues, and by inviting 100 guests within the exhibition period of 100 days, amongst them: Agamben, Balibar, Enwezor, Farocki, Koolhaas, Ruiz, Said, Sassen, Spivak, Van der Keuken etc. The next one, Documenta 11, was located at five different places, called platforms, a word that summarizes and symbolizes the encounter and exchange of art communities. When we look at the titles of these platforms that took place in Vienna, New Delhi, St. Lucia (West Indies) and Four African cities, we get the impression of a political mission. The co-curators of this Documenta had a background both within as well as outside the Western World. The main idea of Roger M. Buergel, the leader of the last Documenta, Documenta 12, can be derived from what he said in an interview on German television (in Aspekte): “we found ourselves fascinated by a new motif: the migration of form. As a traceable movement of form from one place to another through geography, time and media, the migration of form shows at the very least that globalization is an old phenomenon.” On a photo taken at the stairs of the Fridericianum building in Kassel we see the multicolored ‘collection’ of the artists he selected (figure 1). This curator poses questions that are literally written on a blackboard as in a school, a place of learning. So the three last Documentas started with learning about cultural differences on an academic, theoretical level, and ended with the idea, not of otherness and cultural difference, rather, with the insight: we share at least specific forms.

Figure 1. From the photo album of Marina Abramovic, 1980. Source: Marina Abramovic. Artist Body. Milan, 1998, 435.

Cultural Nomads: Manifesta and Johannesburg Biennale

Artists and guest speakers of these Documentas have of course different opinions about the effects of globalization, but they also reflect different positions. Although Documenta is still the most important perennial international art exhibition, it increasingly has to contest its strength with the 112 contemporary art biennials, of which is stated by Emmanuelle Lequeux (Le Monde 09/06/2007): “the multiplication is exponential, testifying to the rampant globalization of contemporary art.” Ever since, many biennials have become a primal locality for a dialogue between first, second and third world countries. An exceptional phenomenon in this context is Manifesta, a traveling European biennial for contemporary art that was founded in 1996 as a response to the new political and social realities of Europe, in the hope to establish a better dialogue between East and West. The first edition, hosted in Rotterdam, focused on issues of migration and cultural nomads. The last Manifesta was in Northern Italy, instead of Nicosia, Cyprus; that plan was cancelled for political reasons.

Regarding curatorial practices, there are always certain exhibitions which seem somehow more telling than others regarding the state of the art world. Such a moment was the Second Johannesburg Biennale (1997), which was addressed the following topic: trade routes, history and geography. It was curated by Okwei Enwezor, the later director of the Documenta 11 in Kassel, and intended to deal with questions about the nature of artists and curators who function as global citizens, and in their footsteps, the audience that follows them on their travels worldwide. In 1997, 160 Artists from 63 different countries traveled to the faraway city of Johannesburg. At the time, South Africa was mainly known by the acts of The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the efforts to come to terms with the past, to move beyond apartheid and to master the anarchy in the cities and more specifically, in the townships. The Biennale however did not concentrate in the first place on the national troubles but addressed transnational issues. To quote Enwezor: “I decided to invite curators from different parts of the world, and my only restriction for them was that it would not be nationally-based. (…) I want them to go beyond their own territorial proclivity. I invited Gerardo Mosquera from Cuba; Hou Hanrou from China, who now lives in Paris; Yu Yeon Kim, based in Seoul and New York; Octavio Zaya from Spain, who has worked with European, Latin American and African artists and who lives in New York; Kelly Jones from the USA; and Collin Richards from South Africa.”(3) He invited curators that already had proved themselves to be global citizens, to be collaborators. Together, they almost covered the entire world, if not countries, than at least continents. Of course, in the first place they were chosen for their qualities as curators and their respective networks, but as the quote implies, these networks were the networks that connected not only different cities, but Western and Non-Western Worlds. Their networks structured a new network, and constituted for Enwezor in second instance an operational field. Enwezor wanted this Biennale to investigate problematic terms such as post colonialism, multiculturalism, and globalization. Let me quote him again: “We wanted to see if people actually do cross those borders as we always believe that they have. At the edge of very extreme nationalisms, we want to explore what the role or what the situation is of being a citizen in the particular context of shifting political landscapes.”(4) Are these curators themselves not the citizens Enwezor talks about? Maybe it goes even further than that: should their living conditions not be the living condition of the global citizen?

Glocalization

My topic, survival kits as shelters, has some affinity with the themes of the Johannesburg Biennale and the first Manifesta. The examples of artistic projects I will discuss here were however not created in the context of these exhibitions. Nor do I wish to present them as illustrations of curatorial themes, not in the least because when it comes to thinking about globalization in the field of art, the voices of the curators and the concepts of the perennial exhibitions seem to dominate the debate.(5) My examples come from the visual arts as well as fashion and architectural design, or better to say, mostly from the space between them. My selections are based on other criteria. I looked for art projects that reflect different positions, even though the first impression, and in a certain sense, also the last impression, would suggest resemblance (see my conclusion). As I suggested already in the beginning, the topic focuses us on a rather limited approach of globalization. Still I think it is a useful approach to investigate what interests me in general, which is: what stances do artists take in relation to globalization?

One of the key concepts of my research in general is glocalization, even more so than globalization. It is related to my hypothesis that most artists, as I mentioned before, if they are at all concerned with issues of globalization, they are still primarily concerned with how the local permeates the global, or vice versa, and how they should relate to the specific, cultural as well as physical conditions of a certain time and place. ‘Think global, act local’ or “the globalization of the domestic and the domestication of the global” are just a few expressions that reflect this idea of glocalization. The first is an assignment, the second is more than just a word play. Glocalization is a term which, just as the term globalization, initially comes from the field of economic analyses. The concept of glocalization was coined by Roland Robertson in his article ‘Glocalization: Time Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity’, an article published in 1995 in the book Global Modernities (ed. Featherstone, Lash, and Robertson). He took it from a Japanese concept ‘dochakuka’, a term referring to the profit one can have of adapting the marketing campaign of a product to each culture or locality. For Robertson it means the simultaneity – the co-presence – of both universalizing and particularizing tendencies. I am not sure if this concept can be transferred properly to the domain of art in all cases. At any rate, in doing so, it gains new meanings. While in the economic sphere, it is often concerned with the clash of the local and the international, with the necessity of bridging cultural differences, in the art world, one often assumes from the outset that differences can lead to a peaceful enrichment or cohabitation of cultures. Of course, this is not always the case, and the examples I will discuss show different ideas: critical points of view, a refusal to adapt to the demands of globalization, or in other cases an armoring (which is something different than a refusal to adapt), against threats in daily life, caused by the effects of globalization. There is at least one other option about that I won’t discuss here – and that is a disavowal that leads to a representation of traumatic experiences.

Marina Abramovic/Ulay

My first example is not particularly relevant for the situation of the last two decades, but does reflect a position we probably all know, because in a way, it still expresses a romantic view on nomadism: the idea of mobility as a necessary condition of personal, or rather, mental freedom. It is also related to the idea that by undergoing a rite de passage in other cultural conditions, one will be able to reach a state of catharsis or sovereignty. I remember quite well the life Marina Abramovic and Ulay were living in the second half of the seventies and early eighties. Marina Abramovic, born in Montenegro, came to the Netherlands in the mid-seventies and Uwe Laysiepen, born in Saarbrücken Germany, already migrated to the Netherlands in the sixties. They had no home, no house, but their Citroen house-bus as they called it, which they traveled around in. And in the periods they left Europe, and lived in Tibet and Australia, they had hardly anything besides the clothes on their backs. They lived for a year with the Indigenous Australians, as nomads. A remarkable physical survival kit used by the Aborigines were their animals (figure 1). But that was not enough for these artists. Their training of meditation practiced by Tibetan Buddhists and the Australian Aborigines themselves, can be seen as another survival kit. Ulay describes this Aboriginal culture as non-materialistic and non-religious, even though they have rituals, and an essential feature thereof: the repetition of actions. For the artists, as wells as for the Aborigines, rituals serve as survival kits. They enforce your strength and structure your behavior. This was their experience as a result of their nomadic travels and encounters with Tibetan Buddhists and Aboriginals, who they later brought to Amsterdam for a theatrical performance: Positive Zero.

On a dramatically lit stage, six Tibetan Lamas in traditional robes presented a concert on chanting and in a separate sequence, two Australian Aborigines in ceremonial body paint played the didgeridoo. In the same year, 1983, also two of their mentors, an Aborigine and a Tibetan Lama, had joined them in Nightsea Crossing at several places around the globe, in an exercise in silence and motionlessness. This was not yet the world as we think of it in the age of globalization, perhaps more a prelude of the world of Magiciens de la terre, the famous exhibition in Paris in 1989. This path of discovery could rather be considered as an escape from reality, the reality of the modern world. However, they brought their experiences back to the modern world and tried to show how one can survive, learn to accept things as they are and live in the present. With Positive Zero, and the specific edition of Nightsea crossing, they achieved an encounter of different cultures, presented in all their richness.

How will we summarize their position in relation to globalization? Certainly a critical stance: the idea that in the modern world man is alienated, that mind and body have been separated, and that we could find the things we have lost, retained in other cultures. These are cultures that the artists refuse to call primitive, denouncing the word the MOMA in New York still used for their infamous exhibition in 1984. Abramovic and Ulay armored themselves, but armoring should be placed between brackets because it is an armor which does not provide any protection, besides the mental and physical Self. Their projects would not have been imaginable without the idea of nearness in a globalized world and the possibility of cultural exchange.

Absalon

But to avoid the implication that everything can now be seen as a survival kit, I will turn to some physical examples such as the Israeli-French artist Absalon, who died at the age of 26. Absalon is known for the structures he fabricated, which could easily be build all over the world. Among them were the Cellules (1990), Proposition d’habitation (1991) and Solutions (1992). Before his death in 1993, he constructed six of these wooden and cardboard models of roughly the same size, but with different ‘furniture’ (figure 2).

The Cellules – austere, white one-person dwelling units – could literally be seen as archetypal living spaces, shelters from the outside world, but also as ‘mental’ spaces for concentration and seclusion. Although he spoke of personal freedom, which could be obtained by these mobile homes, this freedom was based on very restricted, closed, almost claustrophobic structures. This becomes apparent when one is able to watch the video in which he moves within those spaces. In de Appel in Amsterdam, his work was presented together with the work of the American artist Elaine Reichek, who researched the dwellings of native peoples, such as those of North American Indians. Her work entails the use of photographs to show how the indigenous people lived and how this was documented by the dominating powers. Her woolen tents were hand-knit on the basis of information from the photographs. This example fits into what Hal Foster called ‘the artist as ethnographer’, which I think is an important paradigm for the issues which we nowadays relate to globalization and glocalization.

By bringing Absalon and Reichek together, the contextualization and interpretation of his work as presented in de Appel changed. From an architectural experiment with a psychological dimension it was turned into a project dealing with a general human social condition. This recontextualisation of his work, also in the context of art and globalization, continued afterwards, perhaps partly due to his untimely death. It is obvious that is hard to define his work in terms of positions within the glocalization debate or global politics, if you take seriously the conditions under which it was originally developed. It brings together opposites, and I think also oppositional opinions about human conditions, in one concept of survival. My next example is quite different, because it is explicitly concerned with specific political circumstances.

Figure 2. Absalon, Cellule no. 1, 1992.

Migration: Los Carpinteros, Hussein Chalayan and Kimsooja

Los Carpinteros is a group of three male artists that started to work under this name in 1994, the year Absalon’s show was in De Appel, and also the year of a Havana Biennale. Their strategy, as they called it, was to slip back into their Cuban homeland after most of the artists had migrated to other countries. “The concept of ‘a carpenter’ was a form of subterfuge for us; it gave us something to hide behind and therefore to circumvent the prevailing climate of vigilance.”(6) They did not want their work to be censored and therefore they cloaked it in “a mantle of manuality and manufacture”, without losing sight of the cynicism of this move. They are maybe best known for these movable cities, consisting of nylon and aluminum in the form of recognizable buildings; all components of a city. They can also be interpreted as a kind of refugee camps, considering the political situation of Cuba (figure 3).

Figure 3. Los Carpinteros, Ciudad Transportable, 2000, 7th Havana Biennial.

The political situation on another island, Cyprus, motivated Hussein Chalayan to one of his best known dresses and installations. He himself was born in Cyprus and was confronted at an early age with the displacement of the people after the invasion of the Turks in 1974, resulting in the division of the island. When the Kosovo war started, much later, he felt the need to respond to the traumatic situation of his homeland. So his work was a reaction, not to a personal, but to a more general situation of being uprooted, especially as a result of wars and forced migrations that often go hand in hand with them. For his 1999 and 2000 collections he designed imposing dresses that were meant to express these situations on a more symbolic level. One example was his chair-dress, whereby a woman could carry her environment along with her. In After Words (autumn/winter 2000) he transformed the clothes and the few pieces of furniture into a theatrical setting with five actors and four models, in an otherwise white space (figure 4). An apron became a cape, a chair cover became a dress and the table became a skirt.

The stage scene concluded with the chairs being folded up into a package that left the stage as a suitcase. In the background, people could hear a Bulgarian choir singing. In a later installation presented in his show in Utrecht, called Woman By (2003), one of the objects was a boat in the form of a coffin, a metaphor for the fear of death, but also a reference to Noah’s Ark, as sign of hope and survival. The next examples also have to do with the theme of mobility and surviving in the world of today, but are not directly related to particular political situations.

In the work of Kimsooja migration plays also an important role, and again, it has to do with her personal history, though not so much directly with political circumstances. Already as a child she lived a nomadic life in which all her possessions could be folded up or easily taken with her, a kind of life which in a way she continued later when, as an international artist, she became part of two worlds: Korea, where she came from, and the international art world. She makes sculptures, installations, and performances in which she appears, for example, as a Needle Women, Mirror Women or Beggar Women.

Figure 4. Hussein Chalayan, Afterwords, Autumn/Winter 2000.

In the installation A Mirror Woman: The Ground of Nowhere she installed a fabric column in the opening of what had been the glass roof before (figure 5). On the floor inside the column she placed a mirror. People who entered the column saw the reflection of the sky in the mirror, but a reflection which not really represent the sky, but was experienced as a rolling sea as well. There was a merger, so to say, of the sky above, and the water below. Yet this experience of alienation was also present on another level, namely that of the identity of a migrant. This installation was made for a specific occasion: the celebration of Korean immigration to the US. So this context, historical event and location, were important too, for the conceptualization of the work and its interpretation. It is my impression that this feeling of alienation in her work goes hand in hand with a feeling of reconciliation with her life as a Korean woman, and maybe also as a globetrotting artist. That makes her position quite opposed to the ones discussed before.

Figure 5. Kimsooja, A Mirror Woman: The Ground of Nowhere, Hawaii/Korea, 2003.

Protection: Final Home and Studio Orta

It is remarkable that once again we find our examples in projects that are situated in the spaces between visual art, fashion design, and architecture. Most of the examples are from around 1994, the year I mentioned before in relation to Absalon and Los Carpinteros. A good but also a exceptional example is Final Home by the Japanese artist Kosuke Tsumura, who in 1994 started with survival clothing, followed by igloo tents and more than ten years later, clothing for a mother who is pulling a cloth pram with, her baby in a kangaroo pouch in front of her stomach (figure 6). Tsumara became known as the designer of a transparent nylon coat with up to 40 multifunction zip pockets. The coat has a grey cord along the edge of the hood to tighten it and grey elastic sewn into the cuffs. A double grey zipper runs vertically along the front of the coat in addition to a single zipper on the left of the coat, and a single zipper on the right. A white fabric tag is sewnonto the right hand side of the coat with an area to write the owner’s name, date of birth, sex, blood type, address, phone number and emergency contact number.(7)

After developing a prototype, Tsumura himself spent several nights sleeping in New York City’s Centennial Park trailing the warmth and comfort of his coat, which he conceived as an final home in the case of a natural or manmade disaster. Tsumura describes it as “a cloth which can be adapted according to need”. For example, to protect against the cold, the wearer can stuff newspapers into the pockets, or they can equip it with survival rations and a medical kit, or even with soft toys which can be used to comfort children so they won’t be scared in case of a natural disaster. The coat, as we now know it, came in three basic colors: ‘orange’ to remind of one’s existence; ‘khaki’ – I prefer to say military green, the color of camouflage – to blend in with the forest and ‘black’ or ‘grey’ to assimilate in the city. Directions for use are written on the bag containing the coat. The name Final Home was first given to this particular garment, and then it became the brand name – it equates to the idea of it being the ‘ultimate shelter’. Final Home’s creations include a poncho which doubles as a bicycle cover, a momoko doll, cardboard sofas, pocket sofa covers and chocolate candles, all designed to aid survival in various conditions in urban life. Final Home promises their buyers that if they bring their Final Home purchases to their outlets at a later date, they will donate the revenue to a NGO for the benefit of refugees or disaster victims. As I said, this is an example of an artist who does not reflect on specific political situations, but perhaps I must correct myself. He deals indeed with all the general phenomena of modern society, and the state of this world, but the humor involved made me think about the Japanese habit of wearing surgical masks because of fear of pollution or viruses. They are serious designs, because they are made to sell, and are indeed functional and even recyclable. But the double meaning makes that they transgress this utility function. The next example concerns a well-known couple in the art world. There is some resemblance with Final Home though the irony and sensible attitude seem to be absent.

Figure 6. Final Home (Kosuke Tsumura), Mother, detail, 2007.

In 1991, Lucy and Jorge Orta set up a studio in which, besides themselves, many different curators, architects, engineers, designers and musicians were working. Lucy, born in England, is a fashion designer. Jorge is an Argentinean artist. In their work they express their concern for the urban environment, for instance, regarding the lack of protection from all sorts of dangers such as pollution. At various levels and for different circumstances they designed objects that offer protection, from special clothing to tents or igloo-like constructions that are shown in installations, performances and on catwalks by a group of users, who are brought into a physical relationship with each other. They started long before the anti-globalization protests started in 1999, after the American refusal of the Kyoto treaty. A few of these projects with which they became known in the early nineties include: Refuge Wear, Survival Kits and Nexus Architecture (figure 7). Stephan Cairns said about Orta’s work:

They contest taken-for-granted conditions of contemporary urban life: displacement, exile, poverty, homelessness. Her projects are never merely utopian because they are both ‘mythic and real’: they are realized, fabricated and deliberately situated in the city, but sustain a mythic aura because they resist the realist, propositional mode of the architect, urban designer or planner. Suspended in this space between reality and myth, Orta equips and choreographs her urban subjects such that they stand witness to the troubles of the world. Orta’s projects disturb our received picture of the world and solicit us to attend to it anew. Like Foucault’s heterotopic spaces, they are catalysts for new attitudes to the city and the way we live in it.(8)

Figure 7. Lucy and Jorge Orta, Urban Life Guard, 2002-2007.

His opinion about their work confirms what my other examples already showed: if not reconciliation, at least in a creative way they bring opposite approaches together. This heterogeneity makes their criticism of social, environmental and humanitarian issues as mobility, population migration, climate and environmental crises, and human rights, not less clear, as for example we can see in their Antartica expedition. In 2007 they went to Antartica on an artistic and social research expedition. When they came back they showed their hand stitched tents, survival kits, videos and mobile aid units on several exhibitions. This Antarctic Village, as it is called, consists of 50 dwellings that bring out the images of refugee camps as we know it mainly through the images on TV (figure 8).

When we think about Antartica, the ecological situation there is one of the first things that comes to mind. However, the Ortas refer to Antartica as a common territory, as it is decided in the Antartica Treaty of 1959. The temporary encampment was envisioned as a free, neutral territory in a place where living conditions are so extreme that it imposes a situation of mutual aid and solidarity, no matter your nationality. The tents have sections of flags from around the world, along with clothes and gloves, symbolizing the multiplicity and diversity of people. There were numerous other activities belonging to this project, such as a football match between Argentina and Great Britain, and the design of a passport for a land without borders. Their work is maybe a good example of how criticism, armoring and efforts of reconciliation – call it solidarity – can go along with each other. I said that there are some resemblances with Final Home, as there are with Los Carpinteros. But while Final Home’s message could be summarized as ‘be always prepared in this world, we help you to survive’, the comments of the Ortas, Hussein Chalayan en Los Carpinteros are much more specific. Chalayan a migrant, Los Carpinteros living like many Cubans in exile. None of them accepts reality as it is, or stresses the benefits of globalization. The next example however takes recourse to a way of communication which is part of the globalized world of the world wide web.

Figure 8. Lucy and Jorge Orta, Antartica, 2007.

Personal care: Regina Frank and Alicia Framis

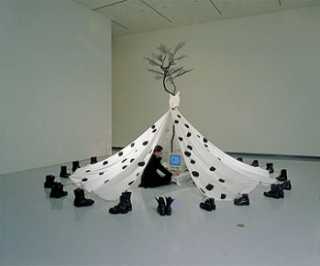

There are many examples of artists who use the igloo or a tent as a home and at the same time as a metaphor. One of them is Regina Frank. She presents her work under the heading ‘The artist is present’, but this presence is partly virtual, partly mediated. The tent, a wigwam, is at the same time a dress, a symbol of femininity (figure 9).

The dress is supported by a tree of black coral, and at the foot of the tree she put black boots to keep the wigwam in place. For three days and nights she stayed in this homedress before returning back home, from where she sent one message a day to the exhibition space, for a total of 97 days. These messages were printed in the wigwam and hung under its roof, which was also a skirt. In this way, a kind of tree of letters was growing that the visitors could read and respond to, also by e-mail. In her installations, Frank continuously shifts between the private and the social, between the digital or virtual and the analog, between political, cultural and spiritual themes. There is some resemblance with Marina Abramovic, who had some influence on her, especially Abramovic’ later work, more in fact than with the Ortas.

Figure 9. Regina Frank, A-Dress, 1996.

The dress is supported by a tree of black coral, and at the foot of the tree she put black boots to keep the wigwam in place. For three days and nights she stayed in this homedress before returning back home, from where she sent one message a day to the exhibition space, for a total of 97 days. These messages were printed in the wigwam and hung under its roof, which was also a skirt. In this way, a kind of tree of letters was growing that the visitors could read and respond to, also by e-mail. In her installations, Frank continuously shifts between the private and the social, between the digital or virtual and the analog, between political, cultural and spiritual themes. There is some resemblance with Marina Abramovic, who had some influence on her, especially Abramovic’ later work, more in fact than with the Ortas.

The last artist I would like to discuss is Alicia Framis, a Spanish artist who lived in the Netherlands. She became well known for her project Dreamkeeper. With the message: “Suffering from lonely nights? Phone the Dreamkeeper”, she was wandering through the streets with her sleeping mat wearing her star dress and moon shoes. “If you made an appointment she came to you. For twelve hours she then stayed by your side. As long as you didn’t sleep, she watched. In the morning she picked up her mat and left again.”(9) Her work has been called ‘social sculpture’ or ‘new performance art’. Here again, a comparison is made with Marina Abramovic, the younger Abramovic, who also placed herself at the public’s disposal and created direct physical contact under vulnerable conditions. Framis searches for, in her own words: “what the people of today, lonely people in the big city, ‘need’, depending on the situation and the place”.(10) What is needed is, according to her curator, intimacy, content, imagination and poetry. In particular, one of her works, the Anti-dog project, shows similarities with the work of the Ortas, especially with the projects that were dealing with metropolitan experiences such as surveillance and police force. The Anti-dog project consisted of a collection of nine gold dresses based on famous designs, such as by Chanel, Dior, Courreges, Gaultier, Hussein Chalayan, Karen Park–Goude and three designs made by herself (figure 10), which she had produced in a particular bulletproof, fireproof and dog proof material. One design is highlighted because it has a double meaning; it resemblances a burka.(11)

Conclusion

Of course, these are only a few examples and the different positions do not cover all the possibilities. I want to remind you that I paid more attention to critical stances and less to the more traumatic, personal expressions of living in a globalized world. And because the theme was Survival Kits, it is not surprising that artistic projects that have welcomed the global world with unconditional enthusiasm have stayed out of sight. In spite of all the differences, most of the projects I have discussed under the headings of migration, protection and personal care show two faces at the same time. For Los Carpinteros, Hussein Chalayan and Kimsooja, the one face is that of being mobile, but that still connected emotionally to a homeland. Absalon, Final Home and Alicia Framis emphasize the protection of personal freedom or safety, but in claustrophobic structures. Final Home and Alicia Framis offered efficient solutions for what can be traumatic experiences. Framis also made objects for protection, but if they did not have this bright color, they would have looked quite aggressive. Nonetheless, the fact that they do have this color and are based on fashion designs presents another face than the face of something meant only for survival. The same ambivalence counts for the projects of the Ortas, Final Home and Hussein Chalayan. From a quite different angle the architectural dwellings of the Ortas, Regina Frank and Los Carpinteros, also show two sides, as they are all based on well known traditional archetypes, but have a ephemeral, temporary or fragile existence. Most of these survival kits have something down to earth, but that is not their sole or most important significance. They also express the need or longing for safety, the way a house can offer this to you.

Figure 10. Alicia Framis, Anti-Dog, 2003

(1) During this conference the G20 gathered in London. The world leaders agreed on one thing: that protecting national economies would make the financial crises worse, at least in the end. There is only a global and not a local solution for a global crisis. (2) These quotes are from Aspekte program on German television, Sunday June 17 2007. (3) Interview with Okwui Enwezor by Pat Binder & Gerhard Haupt, Johannesburg 1997. See: http://www.universes-in-universe.de/car/africus/e_enwez.htm

(4) Ibidem

(5) One could ask if the attention paid to curatorial practices is caused by the fact that ‘theory’ is located here. This question was raised through the lecture of Ruth Sonderegger at the Gimme Shelter conference. (6) From an interview with Los Carpinteros by Rosa Lowinger, Sculpture Magazine. December 1999, Vol. 18. No. 10. (7) This precise description is taken from http://www.dhub.org/object/351991,japanese+fashion. (8) Stephan Cairns. “My Own Public Heterotopia”. Published for the 9th Havana Biennale 2006. See http://www.studio-orta.com/media/text_34_file.pdf.

(9) http://www.smba.nl/en/newsletters/n-35-the-dreamkeeper/ (10) Ibidem (11) This same ambiguity one can see with Vexed Generation that developed parkas and jackets that protect the person who wears it against all kind of threats in urban life, but the parkas themselves look very intimidating.